Politicizing Climate Doomism Part 4: The Carbon Tax!

In this article I argue that the economics profession has implicitly estimated that human life of young people is probably worth a few thousand dollars.

It is the year 2025, and I think we can safely say that the carbon tax and Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) approach to climate change is considered highly inadequate by all except industry shills and cave dwellers. It’s all history at this point. And the debate is largely between green growth and regrowth™ these days. So what I'm discussing here in this article is an overview and history of how the carbon tax was shaped as an anti-solution, in order to mould the public mind towards fatalism, which is defined in the literature as:

The perception that climate change is unstoppable, inevitable or otherwise unchangeable by human action.

This definition is broader than the one I started with when writing this series, (which was Michael Mann’s). If that’s shifting the goalposts, then I feel justified in doing so. The definition of climate fatalism needs to be used here because its generality allows me to yield more insights.

The carbon tax has been used as an anti solution in the following ways. One, at least 3384 economists have argued in favour of limiting climate action to just a carbon tax. Two, the carbon price has been massively underestimated by most economists in environmental economics.

Combining these first two points is a form of tacit solution denial. By limiting the scope of the solutions, a segment of the public would think that we cannot achieve the Paris Agreement’s targets of well below 2 degrees. Which is actually a logical conclusion to make given the lies they’ve been told.

Because a small carbon pricing means we only offset a small part of emissions when planting a tree, this means that pretty much everyone who uses carbon credits has always been aiming for a “net positive” future rather than “net zero”. A “net positive” future is likely what the Climate Change Commission is aiming for given their policy advice. It’s definitely what the labour party has aimed for. And it’s very obviously what the National party has aimed for, when you do the math.

Three, the carbon tax is framed in a regressive way, meaning poor people are to pay for it. Four, thanks to the work from Greenpeace, we know that the reason ExxonMobil and other fossil fuel companies supported a regressive version of the carbon tax, is because they know it will make people hate the carbon tax and think that we simply cannot solve the ecological crisis without harming people. These four reasons combined can contribute towards the fatalist attitude towards climate action.

Let's improve society somewhat (but not too much)

Mainstream economics uses the concept of an externality to describe an effect that happens when two people make a market transaction. Such effects can be good, or bad. If you actually try to understand how the economy works, you will soon realize that almost the entire economy is just a bunch of externalities. One of these externalities is considered to be a catastrophic risk to civilization.

Given the significance of externalities, you might expect that a third of your first year microeconomics course would be dedicated to discussing them. The reality is that they are usually discussed for no more than one lecture. I think if first year economics was going to teach one thing about the environment, it would be the Jevons Paradox. It is both easy to understand, and in my view the most relevant and useful idea to come out of neoclassical economics, in relation to the ecological catastrophe.

One convincing reason to me for the narrow discussion on externalities is for political reasons, where historical context can be found in Oreskes and Conway in “The Big Myth”. This book describes a century-long history of business elites promoting the mythology of free market fundamentalism, and their attempt to shape the economics curriculum. One influential figure here was Friedrich von Hayek. Admittedly, I haven't read his work The Road to Serfdom. According to Oreskes, Hayek was not quite the free market fundamentalist that he is often portrayed as. He was actually in favour of pretty heavy handed regulation of externalities:

What sorts of interventions were legitimate? Hayek specifies a surprisingly large number. They include paying for signposts on roads, preventing "harmful effects of deforestation, of some methods of farming, or of the noise and smoke of factories," prohibiting the use of "certain poisonous substances or requiring special precautions in their use," limiting working hours, enforcing sanitary conditions in workplaces, controlling weights and measures, and preventing violent strikes. (Oreskes & Conway, 2023)

This mixed economy approach of regulating or taxing the externalities from Hayek was later watered down by the economist Milton Friedman:

Friedman defines neighborhood effects as circumstances where "the actions of individuals have effects on other individuals for which it is not feasible to charge or recompense them... An obvious example is the pollution of a stream." Friedman's use of the idiosyncratic and friendly term neighborhood effect—rather than more common negative terms such as external costs, negative externalities, damages, and nuisance—signals his attitude. (Oreskes & Conway, 2023)

The obvious example of stream pollution has since become more obvious in New Zealand. So perhaps we can forgive Friedman for not quite understanding how big these externalities would become. It was the 1960’s after all. Given this early failure, we might have expected the economics profession to become more heavy handed in discussing externalities as time went on.

Most economists think of themselves as quite progressive these days, but once you expand the historical scope to see what generations of free market fundamentalist ideology has done, you can see that it’s still pretty entrenched. The effect of Friedman’s conception of the economy is still visible in the undergraduate curriculum, and much of economic thought.

Here is an example of a letter in 2019 signed by thousands of economists, and 28 Nobel prize winning economists. The letter can be interpreted as arguing in favour of climate inaction, by limiting the solutions to a carbon tax. Note the following condition:

A sufficiently robust and gradually rising carbon tax will replace the need for various carbon regulations that are less efficient. Substituting a price signal for cumbersome regulations will promote economic growth and provide the regulatory certainty companies need for long- term investment in clean-energy alternatives.

In fact what actually built the renewable energy sector in the two decades prior to this letter was public money via development banks, and feed in tariffs. Germany was the most successful example of that.

Perhaps some economists signed it with reservations. But there’s an absence of more progressive economists (Nicholas Stern, Joseph Stiglitz) signing this letter, and I think the reason is likely because the above principle says we should limit action on climate change.

Underestimate the price of carbon (on purpose).

Most researchers in environmental economics have deliberately underestimated the pricing, by a factor of at least 10x, up until the last couple of years. If you talk to economists about the main culprit here, William Nordhaus, they will say that this guy was an outlier. Even some of my heterodox economist friends I talk to make up this alternate reality when I probe them. Nordhaus wasn’t an outlier, though he did lead much of the subfield astray.

The likes of Nordhaus and those that were led astray were told several times, right from the beginning, that their methodology was flawed. Both from physicists like Alvin Weinberg (1983), and occasional economists like John Quiggan (1999).

My impression is that, although the profession has changed their viewpoints, it is because they listened to pressure, not criticism. Because the 2018 Nobel prize to Nordhaus brought too much attention from activists, heterodox economists, and experts outside of economics, which made it into the media. The negative attention is partly what shifted such environmental economists to increase their estimates.

How do economists miscalculate the carbon price? They miscalculate this thing called the “Social Cost of Carbon”, which is defined as the cost to society of adding one ton of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Here’s an interesting insight you can get from combining the views of scientists and economists. When you look at scientists who calculate the death toll of climate change, they use this methodology called the “one thousand ton rule”, which argues that it takes about 1000 tons of carbon emission to kill one person. This is how they came to the conclusion that we will kill roughly a billion people this century (mean estimate), if we don’t change course.

From around 1990 to 2020, there were around 6000 estimates of the social cost of carbon, and environmental economists considered the price on carbon to be around $10-200 on average. The ETS pricing in NZ has been on the low end of this:

The ETS finally came into effect in 2008 but the price of NZUs remained stubbornly low due to a combination of factors and government policy. So up till 2020 the price didn’t rise above $35. After fixing up some other problems the Climate Commission managed to persuade government to put a cap on the number of units up for auction, thus causing the price of carbon to rise as far as $88 in November 2022.

By combining the conclusion of the thousand ton rule with the pricing economists came up with, we might conclude that human life is worth around $10,000-$200,000. Nordhaus’s estimate of the social cost of carbon was $31, so life is worth $31,000 by the thousand ton multiplier.

However, when you factor in that many carbon credits are worthless, and NZ used such worthless credits, then also factor in the fact that trees only absorb the needed carbon after a few decades, and that climate change is one of 9 planetary boundaries, we can conclude that the lives of young people are almost as worthless as carbon credits. The science is clear. It shows that the lives of zoomers are not even worth paying a few grand to save.

This pricing aligns well with the farming lobby’s efforts to kill the carbon tax during the fifth labor government. The pain that an extra $300 a year they would have had to pay was simply not worth it. When all the numbers are done and dusted here, it may well be that the average cow is worth more than a zoomer, or at least an alpha:

The following year, it also began consulting on a levy on agriculture to fund research into reducing ag emissions. It would cost the average farm $300 a year — about 9 cents per sheep and 54-72 cents per cow. Farmers, however, labelled it a fart tax and the outcry culminated in National MP Shane Ardern driving a vintage Ferguson tractor named Myrtle up the steps in parliament. The government caved within months.

Recent research in environmental economics estimates the social cost of carbon at $1367 (US), or $2278.77 (NZ). So, how much is life worth now according to economists? About $2.3 million (NZ) I suppose. That’s a big bump. The reason the estimates got a much larger number is precisely because they did not use the selective methodology that the previous social cost of carbon estimates used in the last three decades (see appendix for explanation).

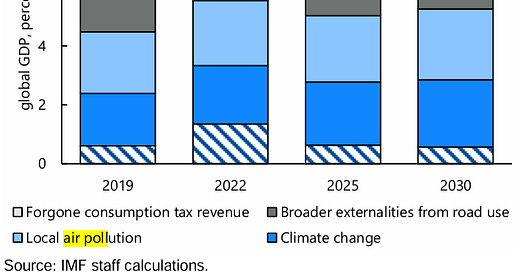

Despite this much larger estimate, they don’t even factor a considerable number of the costs of carbon into their methodology. One glaring omission is air pollution, which the IMF fossil fuel subsidy studies estimate to be comparable to global warming itself.

The underestimations of the carbon pricing (called social cost of carbon in the literature) have influenced policy around the world, including the so called “independent” institutions such as the Climate Change Commission.

To put things into perspective, the Climate Change Commission still recommended pricings of around $100 or less still. So if we subtract $100 from $2278, we have a remainder of $2178 to fill in by using the government faucet and letting the money flow heavily into infrastructure like public transport, dense housing, regenerative farming, ect.

That would be a fine thing to me, because I think the ETS is overly simplistic anyway. But my impression of their 2023 advice to the government is that their government faucet works more like a leaky garden hose, drip feeding money to the public. Reality dictates that we need a firehose to make up for the other $2178+.

Make poor people pay for it

An interesting overview of the history of NZ’s ETS is given here by Deidre Kent. According to this analysis, the “treasury warned that the price of petrol would rise and so would electricity” if we raised the ETS. So one consequence was “late last year (2022) Cabinet rejected the Climate Commission's advice to change settings to let the price go up, citing the cost-of-living crisis.”

The assumptions here are in this analysis and many others is that it the idea that rich people could pay for an ETS is physically impossible.

And that there is something called a “cost of living crisis”, rather than a “price gouging crisis”. Dealing with the price gouging crisis is not a thing, because price gouging is a natural phenomenon, as implied by the euphemistic language of “cost of living”, which neglects to remind us that costs come from rich people.

The consequences behind these assumptions are the Yellow Vest protests in France, when a regressive carbon tax was implemented. One powerful group of actors that seem to have used this phenomenon are the fossil fuel industry. This is discussed in Blakeley’s Vulture Capitalism:

In 2021, a senior ExxonMobil lobbyist told an undercover Greenpeace reporter that the company had been lobbying Democratic senators seen as amenable to the corporation to resist Biden’s climate plans.

The lobbyist described the Biden administration’s plans to cut carbon emissions as “insane” and stated outright that Exxon had “aggressively fought some of the science” through “shadow groups” to protect its bottom line.

The lobbyist also admitted that the company had indeed been backing calls for a carbon tax, which would be levied on consumers rather than producers, on the basis that it knew such a tax “on all Americans” was “not going to happen.”

Conclusion

So there you have it. There’s much more you could criticize about the carbon tax or ETS. But it’s history at this point, and such a boring topic does not deserve more attention. What is required here is for people to understand how narrow framing of policy discussed is used to make them feel that climate change cannot be solved. The three examples should be more than enough to demonstrate this.

Let’s summarize. The first example was the idea of downplaying externalities, which was done by the Chicago School of Economics, and had the effect of limiting the solution space to a carbon tax. Then the price of carbon was systematically underestimated, which was done by Nordhaus and others from the 1990’s onwards. Then shaping the carbon tax to cause political instability, in order to get people to believe that the carbon tax would be financially ruinous.

REMARKS

Regrowth:

I have decided that I shall call degrowth = regrowth instead. Using the word regrowth allows post growth scholars to decode why I’m using the term regrowth, (they get why and understand its the same as degrowth). It also removes the negative austerity connotations that people have of degrowth. This is an equitable compromise between the two, I think. Using sufficiency economics may cause degrowth scholars to say something like: “we literally already came up with that before you did”.

Disclaimer:

I don't want people to get the impression that I'm singling out economists here. The reality is when it comes to the blame game, other social sciences, humanities, and applied sciences should not feel so righteous in ridiculing economists.

Nor do I want people to take away reflexive, punitive ideas towards the university. There’s enough contempt towards science and social science in the current almost fascist society. It is clear that research and development is underfunded, shaped for harm, and academics suffer under the yoke of corporatized administrative bureaucracies. I shall write about possible solutions to that in the future as well.

The future of this series:

I'm going to be generalizing the idea of fatalism towards more than just climate change or the ecological crisis in future articles. That’s always been a goal, to argue that fatalism was largely a political ideology. Where did this motive come from? Mostly it came from my extreme annoyance in reading articles that attributed it to human nature. Another reason is that it is a serious problem, particularly among the young, the poor, and those in the global south. That is not to leave the rich out of it.

Here are some future topics in this series. I want to demonstrate that econ101 promotes fatalistic attitudes in area’s towards public money, employment, ect. I want to argue that political scientists teaching people that we live in a democracy has promoted fatalism in very significant ways. I want to expand on my existing critiques of game theory narratives (prisoners' dilemma) towards other lock-in narratives like competition, capital flight, ect, and how they can promote fatalism. The media of course will get a solid mention as well.

Then I want to discuss solutionism, climate optimism, and strategic responses to promoting optimism.

The methodological error:

The methodological error that is recently fixed, allowing for massive pricing estimate increases, has been discussed and explained in my previous article “Notes on climate change denial in economics education V2, Douglas Renwick, 2025”.

From the paper that updates the error, we have an explanation that notes that most papers had this error, and what it was:

Our analysis suggests that Integrated Assessment Models have historically delivered small costs of climate change not so much because they relied on incomplete foundations, but instead because they were calibrated to economic damages that did not represent the full impact of climate change…

Why are perceptions of climate change misaligned with empirical estimates? Do existing estimates not account for the full impact of climate change, or are its costs truly small? In this paper, we demonstrate that the macroeconomic impacts of climate change are six times larger than previously documented. We rely on a time-series local projection approach to estimate the impact of global temperature on Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This approach exploits natural variability in global mean temperature—the source of variation closest to climate change—which we show to predict damaging extreme climatic events much more strongly than country-level temperature…

We find that a 1°C rise in global temperature lowers world GDP by 12% at peak. We then use our reduced-form results to estimate structural damage functions in a simple neoclassical growth model. Climate change leads to a present-value welfare loss of 25% and a Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) of $1,367 per ton of carbon dioxide.

Bibliography

Academic Articles

Anderson, K. (n.d.). Callous or calamitous: The UK climate minister pulls the rug from under 1.5°C. Kevin Anderson Blog. https://kevinanderson.info/blog/callous-or-calamitous-the-uk-climate-minister-pulls-the-rug-from-under-1-5c/

Mayer, A., & Smith, E. K. (2019). Unstoppable climate change? The influence of fatalistic beliefs about climate change on behavioural change and willingness to pay cross-nationally. Climate Policy, 19(4), 511-523. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1532872

Bilal, A., & Känzig, D. R. (2024). The macroeconomic impact of climate change: Global vs. local temperature. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 32450. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32450

Rennert, K., Errickson, F., Prest, B. C., Rennels, L., Newell, R. G., Pizer, W., ... & Anthoff, D. (2022). Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO₂. Nature, 610(7933), 687-692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01680-x

Tol, R. S. J. (2023). Social cost of carbon estimates have increased over time. Nature Climate Change, 13, 532-536. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01680-x

Books

Blakeley, G. (2019). Vulture capitalism: Corporate crimes, backdoor bailouts, and the death of freedom. HarperCollins.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2023). The big myth: How American business taught us to loathe government and love the free market. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Government and International Reports

Black, S., Liu, A. A., Parry, I. W. H., & Vernon-Lin, N. (2023, August 24). IMF fossil fuel subsidies data: 2023 update. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/08/22/IMF-Fossil-Fuel-Subsidies-Data-2023-Update-537281

Climate Action Tracker. (n.d.). New Zealand. Climate Action Tracker. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/new-zealand/

News Articles and Reports

Greenfield, P. (2023, January 18). Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/18/revealed-forest-carbon-offsets-biggest-provider-worthless-verra-aoe

Organised crime scandal shows NZ's climate policy is a total bloody waste of time. (2016). Greenpeace Aotearoa. https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/press-release/organised-crime-scandal-shows-nzs-climate-policy-is-a-total-bloody-waste-of-time/

Pearson, E. (2024, October 16). Smoke and mirrors. North & South. https://northandsouth.co.nz/2024/10/16/smoke-and-mirrors/

Ripple, W., Wolf, C., Gregg, J. W., Rockström, J., Newsome, T. M., Law, B. E., ... & Huq, S. (2023). COP28: How 7 policies could help save a billion lives by 2100. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/cop28-how-7-policies-could-help-save-a-billion-lives-by-2100-212953

Blog Posts and Opinion Pieces

Kent, D. (2023). Isn't it time to admit the Emissions Trading Scheme will never work? Degrowth NZ. https://www.degrowth.nz/blog/isn-t-it-time-to-admit-the-emissions-trading-scheme-will-never-work

Renwick, D. (2025). Politicizing climate doomism part. Douglas Renwick Substack. https://douglasrenwick.substack.com/p/politicizing-climate-doomism-part

Policy Documents and Statements

Economists' Statement on Carbon Dividends. (2019). Climate Leadership Council.

https://www.econstatement.org/

Videos

Mitchell, B. (2024). The REAL origins of Neoliberalism in Britain Exposed [Video]. YouTube.

Historical References

Horrowitz, J., & Quiggin, J. (1999). The impact of global warming on agriculture: A Ricardian analysis: Comment. American Economic Review, 89(4), 1044-1045. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.89.4.1044

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Press. [References to Singer, F. and Weinberg, A. found within this work]