TLDR:

I argue that saying we live in a democracy undermines democracy.

I use the political science textbook definition of liberal democracy to argue we do not meet any of the conditions.

I expose the sham that is the Economists Democracy Index, arguing that it contrives a definition of democracy in order to justify existing views of democracy. I argue that the Index is completely worthless, and not just “a little bit wrong”.

Fatalism and Democracy

Until Trump's reelection, Political scientists in America have thought that their nation is more democratic than the public does. My experience reading policy journals and the news mirrors this claim. The phrase “liberal democracy” is often used to describe the current political system, and the economists democracy index is sometimes cited to justify this view.

I want to argue the following. First is that the claim that we live in a liberal democracy is harmful to democracy, because it promotes doomism, and it’s not true. Second, I use a political science definition of “liberal democracy” to argue that we don’t live in one, thereby justifying the first claim. Third, I want to give an example of how definitions of democracy can be contrived to justify the belief that we live in one, which supports power. I will go through the economists democracy index and do this.

The second point, that we do not live in a liberal democracy, is not hard to convince most people of. But the purpose of making this claim is to explore the underlying logic behind it, not the conclusion.

I want to distinguish myself from the typical left-winger that cites academic journal articles that justify their view, even if their views are correct. Most people on the left cite the 2014 study by Gilens and Page that argues we live in an oligarchy. I doubt many read through the article however. I will criticize it the study, though for reasons that most people do not. I’ll pick global warming as a single policy and use examples to raise questions about this article.

Fatalism

So why does claiming that we live in a liberal democracy promote fatalism? If we do not live in one, and people are told that they are, then the subset of those people who would want to live in a liberal democracy will have no reason to strive for one.

Even worse, on the condition that they think the current system is a liberal democracy, but don’t like it, what can happen is that they will say they do not like liberal democracy. Under such a scenario, what they really mean is that they do not like the current system.

Anecdotally, I’ve been told by people that they hate democracy. I tell them that I like democracy, but I just don’t think the current system is democratic. Such people have sometimes changed their mind to my view instantly when I add the italicized part. Test it yourself. I need more than just my own anecdotes.

On the condition that we do not live in a liberal democracy, this would imply that a subset of the public is being made to hate democracy, simply by claiming that we live in one.

A response to this is to say that democracy is something that exists on a spectrum, and that we have a democratic deficit. I would agree with this. It certainly exists on a spectrum, and framing it that way can be fine. It is technically true that every single political system can be said to have a democratic deficit though, if you measure it on a spectrum. Such a narrative does not undermine democracy as much as saying we straight live in one. But I think it undermines democracy nonetheless.

It is also the case that political systems can be graded by numbers, and if they go over a certain number, they get a particular name. The economist’s index calls any nation state that’s rated over 8/10 on their spectrum is a “full democracy”.

Most nations call themselves democracies, while are less likely to call enemy nations democratic. China calls itself a democracy. North Korea does too. The Democratic Republic of Congo does. The whole Global North does. It's not hard to see that one of the reasons that nations do this is because of the propaganda effect I have described above.

Because of this, it should require a fairly high burden of proof to claim that your own society is such a political system. At the very least, I think schools and universities should avoid claiming that they understand what system we live in, unless very strong evidence is met.

Teaching kids that we live in a democracy without using definitions is an example of political rhetoric, for example. They must be shown the definitions, and then allowed to decide based on the weight of evidence. This process leads to discovery.

The solution to the current system is in my view “liberal democracy”, and saying that we live in one is straight solution denial. It quite clearly implies that we must choose some system other than liberal democracy if we want to change it

What is the Political System?

It is only fair to let people use their own definition of democracy, so as to avoid contriving definitions to suit your political views. Therefore I propose the following definition, in the undergraduate political science textbook:

One fundamental value is that people have interests and that these interests should be met through the political system. Another assumption is that people are by and large the best judges of their long-term interests and wants. These assumptions support the principles usually associated with what is known as ‘liberal democracy’, the type of government found in western-style capitalist democracies such as New Zealand.

The basic liberal principle is that individual people should be free to live their own lives as they wish, subject always to respecting the similar rights of others. The basic democratic principle is that individual people should count equally and have an equal say in making decisions which affect them (P17, Politics in New Zealand).

Here we have an explicit statement of the definition of liberal democracy. It seems reasonable to me. This definition allows me to say that I'm in favour of it, because I agree with both the ‘liberal’, and ‘democratic’ conditions.

I’ll analyze each principle in turn. First I want to point out that the definition itself contains an inconsistency. If you take the view that people should have an “equal say in making decisions which affect them”, then it doesn’t make sense to even say that nation states are liberal democracies or not. This is because most of the decisions which affect people born today are made by people outside of their own nation, with perhaps America being the exception. But decisions to pollute made by China, Canada, EU, and Russia will have a significant effect on American lives, so the point is made.

An extreme case is the nation of Kiribati, an island of about a hundred thousand people. It will likely not exist in a hundred years, due to it being swamped by rising sea levels. So to even call New Zealand a political system like “democracy” in many ways doesn’t even make sense, because bounding a political system by these imaginary lines doesn’t make sense if we use the two principles here.

Now, one response is to say that we enforce the condition that political systems describe nations anyway, and treat cross border effects as a separate category. I think it’s better to reject this approach on the grounds that it’s less interesting and informative to people. However I still think it’s fine to call all nations by a political system for the purposes of brevity and audience consideration.

The “Liberal” Principle

Consider the liberal principle. That people should be left alone to do as they wish. It rests on the view that people are good judges of their own interest.

The assumption is that people are by and large the best judges of their long-term interests and wants.

This is a nice principle and I agree with it. But I want to argue that in practice, the liberal principle is not applied.

For those who have read Noam Chomsky’s work on the public relations industry, he quotes the founders of this industry as having an illiberal purpose. He quotes Walter Lippmann, who wrote that public relations be used because the “public must be put in its place”, so that we may “live free of the trampling and the roar of the bewildered herd”, whose “function” is to be “interested spectators of action,” not participants.

These principles can be seen in practice in every election, where right wing identity politics distracts from unwanted policy, or empathy rhetoric distracts from lack of policy. The ratio of public relations officials for every journalist managed to skyrocket under neoliberalism (Robert McChesney, Digital Disconnect).

The austerity agenda is similarly founded on these ideas, which are discussed in Mattei’s Capital Order. The Italian economist, Maffeo Pantaleoni called democracy “the management of the state and its functions by the most ignorant, the most incapable”. The incapable public had to be kept out of decision making processes, such as monetary policy, fiscal policy, and industrial policy. The theories that these people created were refined and persist in today’s society.

For example, central banks were justified in the 1920’s to keep inflation and unemployment control out of democratic decision making:

“The Government must answer criticism, for its tenure depends on popular support.” The central bank, on the other hand, “is free to follow the precept: ‘Never explain; never regret; never apologise’” (2022, Mattei).

Similarly, the threat of “public opinion”, which is “largely responsible for the situation”, of the expansion of “public finance throughout the world” was discussed as something that had to be stopped so that they could bring “every country to realise the essential facts of the situation and particularly the need for re-establishing public finances on a sound basis.” (2022, Mattei)

If you read a lot of my writing about various industries, you’ll note that I make a point of it that every single one justifies their climate inaction on “voluntary” or “aspirational” contributions or consumer choice.

Underlying this assumption of voluntarism, often hardcoded as corporate social responsibility (CSR), or environmental, social, governance (ESG), is the view that the public should not regulate capitalist industries. The tacit assumption is that capitalists will volunteer to make the decisions for society, because they know what’s best for society, due to their dedication towards social responsibility. These principles are enunciated the loudest at the World Economic Forum, who call it Stakeholder Capitalism.

The legal framework for climate action has been determined this way as well. The Paris Agreement was made to be strictly aspirational. Less known was the alternative People’s Agreement of Cochabamba, in Bolivia. They offered a different alternative:

We categorically reject the illegitimate “Copenhagen Accord” that allows developed countries to offer insufficient reductions in greenhouse gases based in voluntary and individual commitments, violating the environmental integrity of Mother Earth and leading us toward an increase in global temperatures of around 4°C.

This ruling was made for the Zero Carbon Act in New Zealand as well. High Court Justice Jillian Mallon ruled that the Act really doesn’t legally bind anything other than to aspire to something:

Mallon ultimately sided with the commission and Shaw, agreeing that the purpose of the act was “more consistent with an aspiration rather than an obligation”.

In conclusion, the liberal principle is not met in the current system. Here is a summary of illiberalism is the current system:

The public is too stupid to make decisions on monetary policy -> central banks

The public is too stupid to make decisions on industrial policy -> voluntarism of business

The public is too stupid to make decisions on fiscal policy -> fiscal responsibility rhetoric

The public is too stupid to punish the right people -> aspirational legal system

The public is too stupid to make to any decisions at all beyond spectating -> public relations

The “Democracy” Principle

Now we consider the democracy principle.

The basic democratic principle is that individual people should count equally and have an equal say in making decisions which affect them

We start by recognizing that the illiberal principles that keep people out of economic decision making discussed above, can be seen as a violation of any idea that people have an equal say in making decisions which affect them. Corporations in particular, which many people spend half their life working in, are entirely undemocratic. An overlord makes decisions that govern the wage slaves at the bottom. The rhetoric of “wage labour” is used to cover up this fact.

In government you can make official information requests, but the corporate structure is free to make decisions without public knowledge. Such decisions are kept secret, even if a corporation conspires to turn society into climate change deniers, with the full knowledge that the entire ecosystem will be destroyed.

Therefore having an “equal say in making decisions which affect them” is not met to a pretty extreme degree. Note that the People’s Agreement at Cochacamba asserts that one of their conditions was the “right to exist”. Such a right obviously precedes every other right on the human rights charter, making the entire document pointless, if this “right to exist” is not met. The conclusion from this is that climate policy, which affects everyone, is pretty far from democratic.

Let’s suppose a thought experiment where everyone in the world actually was able to vote on decisions which affected them. Suppose that when you went to the voting ballot, you were able to vote on the elections of every government in the world (or even better, the policies of every government).

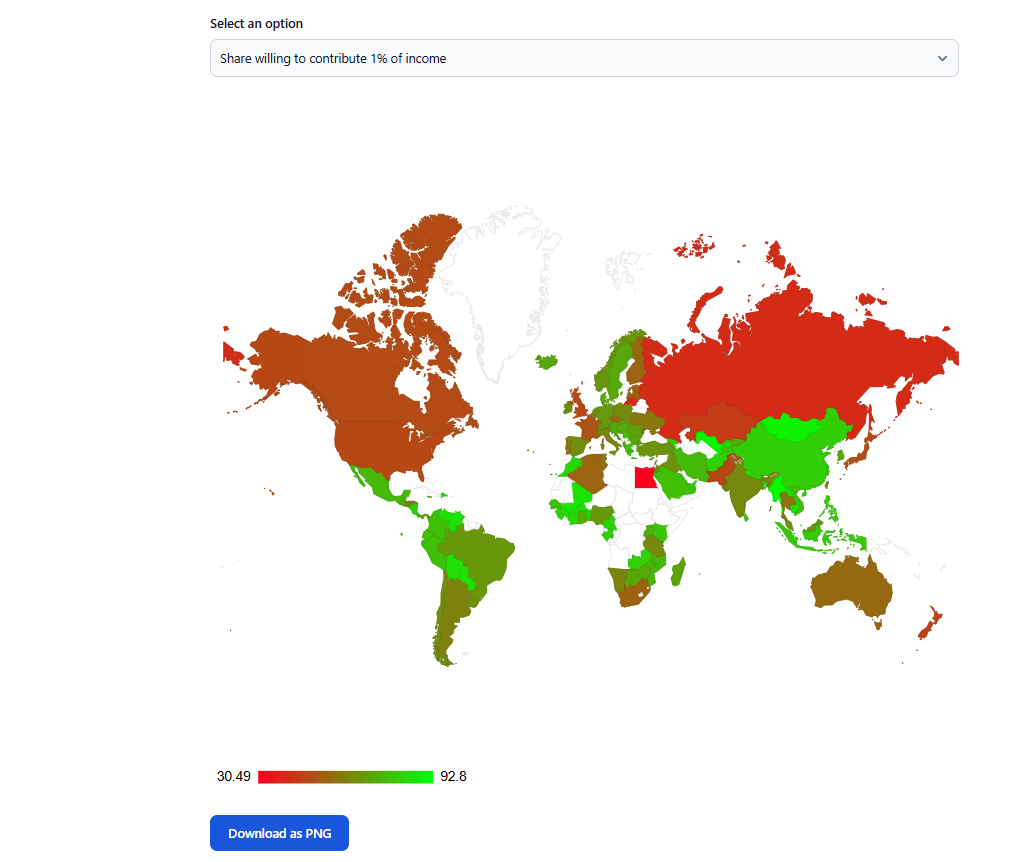

What would be the outcome? The People’s Climate Vote gives a pretty good indicator I think. About 80% of people in the world think their own country should strengthen climate policy. This is much lower in the richer nations. Further, most people in the world are willing to pay 1% of their income out of their own pocket in order to pay for a transition. These people are concentrated in the Global South. What would they say about other people paying out of their pocket?

I want to talk about Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, two political scientists who argued that we live in a kind of business oligarchy in 2014. The study was quite heavily criticized by other political scientists. The criticisms seem mostly irrelevant, and a rejoinder can be found here.

But in my view there are a lot of good criticisms that can be made about it. One I've already made is that the consequences of decisions are not bound by national borders. Their methodology compared policy preferences between rich and poor, when they disagreed. The dataset of policies they used contained around 1800 policies. Only six policies discussed global warming. Two of the questions were framed as denial talking points, such as “replace oil with nuclear”, which comes straight from the ecomodernist tech bro crowd. The other was framed as “jobs vs economy”. The others were on the Kyoto protocol, which almost no one would be informed on. In terms of the weight of the effect that global warming has on people’s lives, you would expect that

The other view they took in their paper was that:

But the evidence that collective policy preferences are generally rather stable over time suggests that expressed collective policy preferences may not often diverge markedly from subsequently manifested “latent” preferences.

What is meant by “latent” preferences could be the preferences that people might have deep down if they were ever asked about it. For example, such preferences might be for a Green New Deal. This was supported by most conservatives and democrats in polling, in 2018. However, a year later, the preference dropped down sharply for conservative voters. Probably that is explained by the Fox News Effect.

So they found evidence of oligarchy, despite not having the ability to test for latent preferences that are distorted by media propaganda, and by having a dataset where only a small part of it is made up legitimate issues that rich and poor people feel very strongly about. And it was confined to national borders.

The problem with liberal scholarship here is that they do not even think about private control over the means of production, which is what people exist in for half their working life. Nor do they even think that the media has much influence.

The Economists Democracy Index

I’ll summarize the Democracy Index from the Economist. It basically does the following. Firstly, it denies the very idea that oligarchy or plutocracy could even be a political system. These are the four political systems that exist on the index.

full democracies,

flawed democracies,

hybrid regimes,

authoritarian regimes

So it starts by framing the system in a way where plutocracy or oligarchy cannot exist. More honest scholarship would categorize the way Aristotle did. According to him, we can simplify it to about three political systems: Autocracy, oligarchy, and democracy. He did not use the euphemism for “flawed” democracy or “hybrid” democracy for oligarchy. Obviously, Aristotle had some shortcomings, like saying that people were wrong to oppose slavery. Interestingly, the democracy index makes a similar mistake, in that the existence of many slaves in a country does not affect the scoring system in any way.

The way the Economists democracy index contrive all their answers is just by doing the following. For each way non western nations undermine democracy, we will survey people and ask them if their society undermines democracy in that way. For each way that western nations undermine democracy, we will not ask almost any questions about that.

For example, all the cases discussed above on public relations and austerity are not asked in any of the 60 questions on the survey. There is one exception, to say that if private property and business is free from government influence, then that boosts your score by one point. So according to the index, it may be seen that austerity actually increases democracy.

No questions about corporate surveillance, just state surveillance. Despite corporate surveillance being a huge part of the economy.

A lot of the questions are just about civil liberties, gender rights, separation of powers, the legal system and the state, corruption, and state torture. Yeah, other countries often score low on these.

There are around 60 questions, and they count for either 0 or 1 point. It’s all quite comparative as well. You score well if you're above the average voter participation. This is how New Zealand is able to score a perfect 10 on participation. But if you actually used the definition of democracy given in the political science textbook, every nation in the world would in my view score about a 2/10 at most. And to be fair, New Zealand might still be at the top of the index, but still be undemocratic.

You really cannot justify anything higher when people cannot or are not voting to have a future though, in my opinion. All of the right’s based questions are worth less than the “right to exist”, which is not met under the current system, and is not discussed on the Index.

So yes, if you read these indexes and treat them as correct, you get a high democracy score. If you follow the definition, which is probably the highest form of rationality ever discovered, used in the sciences, then you will probably get a wildly different answer. Somehow political scientists quote this index as if it even means anything.

Final Thoughts

I wanna come back to the start of this essay and talk about solution denialism. Which has come from not even wanting to understand the political system we live in. If you cannot even do that, then the solutions you propose will be no solution at all. This is why we get ideas like “civics courses”, or “decreasing the age of voting”, and “MMP” as the solutions.

Or you get journalism that focus on the moral failures of Seymour’s Dickensian slop for children. All of this shows a bit of contempt for liberal ideals. If people are the best judges of their own interest, you don’t focus on morals. You focus on getting them to understand society, and see them make whatever decision they will make, because the assumption is that it’s in their own best interest.

Edits:

On the democracy principle, It should be noted that people spend half their life at work, usually in a corporation where they take orders from above. In terms of having an equal say in decisions which affect them, this should be weighted towards being a large factor in undermining democracy. Of course, the economists index does not mention this.

Bibliography

Books

Mattei, Clara E. The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism. University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Mulgan, Richard. Politics in New Zealand.

McChesney, Robert W. Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy. New Press, 2013.

Academic Articles and Studies

Gilens, Martin, and Benjamin I. Page. "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens." Perspectives on Politics 12, no. 3 (2014): 564-581.

Surveys and Polls

https://peoplesclimate.vote/

News Articles and Online Sources

New Zealand Politics and Democracy

"Ingenio Future of Democracy." University of Auckland, October 31, 2022. https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/news/2022/10/31/ingenio-future-of-democracy.html

Edwards, Bryce. "Losing Confidence in the Integrity of NZ Elections." Democracy Project, May 9, 2024. https://democracyproject.nz/2024/05/09/bryce-edwards-losing-confidence-in-the-integrity-of-nz-elections/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/23/critics-challenge-our-portrait-of-americas-political-inequality-heres-5-ways-they-are-wrong/

Climate and Democracy

"Integrity Briefing: Kiwis Are Waking Up." The Integrity Institute.

Historical Documents and Agreements

Climate Agreements

Paris Agreement (2015)

People's Agreement of Cochabamba, Bolivia (2010)

Legal Cases and Legislation

New Zealand Climate Legislation

https://newsroom.co.nz/2022/11/27/shaw-successfully-weakens-own-climate-law/

Reference Works and Indices

Democracy Measurement

The Economist Intelligence Unit. "Democracy Index." [Annual publication]

I think this is a good definition of liberal democracy: “…that individual people should be free to live their own lives as they wish, subject always to respecting the similar rights of others.”

and for that reason I do not wish to live in a strict liberal democracy. I’d prefer some element of socialism as well as in ”in addition to”.

Because some global/communal problems cannot be solved with individualism of this libdem nature. It is well known throughout history that rules-based orders only work well so far as they do not hit unforeseen consequences, so never work far enough. I like rules based orders. But they can sometimes become pathological in certain domains, and some element of collectivism is required as a counter-balance. When enough people rise up to tell the rules chiefs that things are wrong, then the rules can, and probably should, be changed. Even if the change is disastrous, if we do not know the outcome ahead of time, but know just “something” has to change, then the boat must be rocked.

I’d offer the UN as an example. The rule of Security Council veto has to be rebelled against. With extreme intellectual violence (meaning lucid and righteous arguments and affirmative actions, say, actions to violate that rule with extreme prejudice).

If poor decisions are made in some transition, then they too can be changed.

Could you also add a paragraph on workplace democracy too?

It is not like we need to have radical democracy in all things (let my nine year olds vote for what we have for dinner), but where there is a moral/spiritual purpose for democracy, or a democratic element in a system, we should try to get it in that place.