Proposed Solutions for Avoiding an Enormous Amount of Suffering

This is an extended rewrite of last weeks article. It goes over some of the major detail's of the green growth vs degrowth debate in agonizingly pedantic detail.

Contents:

The Current Sentiments of Capitalism

Fascism

Plutocracy

The Centrist Approach to Climate Policy

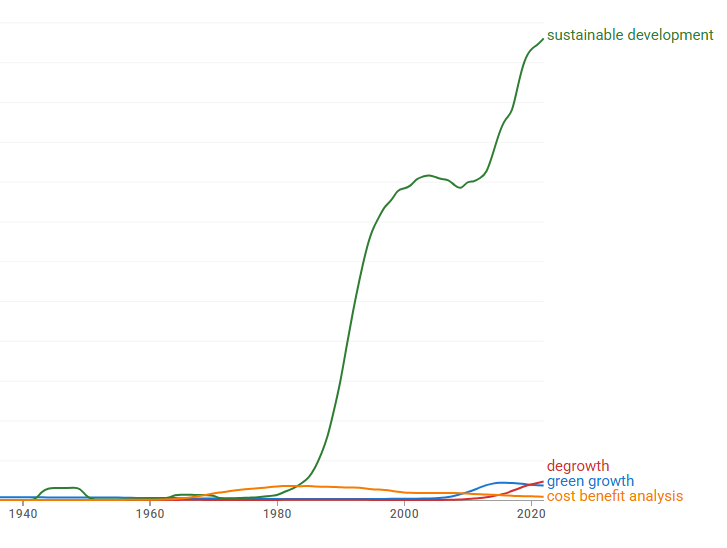

How Green Growth and Degrowth were Suppressed

Suppressing the Green New Deal

An Overview of the Similarities and Differences

Disagreements

Policy Pathways

Misrepresentations from Green Growth

Framing Degrowth

Conclusion

According to the historical record, the capitalist system in all forms has been constantly resisted by the global population.1 If we call the majority opinion of the global population the “centrist” position, then it would be fair to say that a minority of the global population known as the “Global North” have had more extreme opinions on capitalism.2

Opinions change however, and it’s become obvious to most in the Global North that the system they live under is rotten, probably terminal, institutions are lying to them, and it’s all to serve a few big interests.3 In fact, the Global North has become far more pessimistic than the rest of the world. This is despite the fact that the rest of the world is heading towards ecological collapse much faster.

Many solutions have been proposed. Perhaps five of the most talked about solutions being proposed to the current capitalist system that have generated a lot of discussion are:

Fascism

Plutocracy

Centrism

Green growth

Degrowth

The bulk of this article will discuss the debate between the green growth and degrowth proposals. To start with, I briefly consider solutions suggested by fascism, plutocracy, and centrism. Then provide historical context of how both green growth and degrowth ideology were suppressed by power.

Then I move onto the green growth vs degrowth debate, and briefly discuss five questions. What do they agree on? What do they disagree on? What I believe they are wrong or right on? What is the appropriate strategy for achieving their goals? What have been some tactical failure’s in achieving their goals?

There is already an article written by public policy professor Jonathan Boston discussing the similarities and differences of green growth and degrowth. This article differentiates itself in style and content to a fairly significant degree.

My own particular interest in this debate is the economic and ecological crisis. If the ecological crisis is not dealt with, then every other political issue becomes virtually irrelevant. This justifies my focus here.

My formal education in the social sciences is non-existent and I have zero expertise. However, I think the self taught approach will yield a different perspective that has some insight here.

Fascism

While most fascist’s neglect to call themselves as such, there has been a variant of “eco-fascism” or “green fascism” that has been suggested among members of the far right. I choose to associate the Republican Party, Alternative for Germany, and similar parties as fascist.

Björn Höcke, a politician from the Alternative for Germany, the largest far-right party in Germany, argued in 2014 that:

‘by the middle of the twenty-first century we will have reached the carrying capacity of our planet … We must consider what a post-growth economy looks like … We must find an economic form that reconciles ecology and economy, and that is only possible if we overcome this kind of capitalism.’4

This sounds like something I’d agree with, except for the solutions that have been proposed. Green fascists wish to strengthen borders and limit immigration, while further solidifying present hierarchies. Such idea’s are based off preserving racial purity or cultural differences.

Personally, I do not agree on immigration. Countries such as Uganda have invited over a million refugee’s into it’s country, despite having very little wealth to support them. I think the Global North needs to be more like Uganda in that respect, because it’s the morally right thing to do.

On overpopulation we can see that implementing free education, free health, employment, and reducing poverty is argued to have a side effect of reducing emissions. Though the effect of how many emissions are reduced may be quite small:

Reducing population should be seen as a co-benefit to policies that reduce child mortality and poverty; give girls the opportunity to go to school, get an education, and employment; improve access to contraceptives; and empower women to make their own family planning decisions.

One defining property with authoritarianism and autocratic rule that’s inherent in fascism, is that it is driven by extreme insecurity. Because autocrats need society to love them, and scientists do not love autocrats, then they will be punished for it. This insecurity implies that green fascism is a contradiction in terms.

Plutocracy

Plutocracy is the political system where political power has a positive relationship with wealth. As with Trump and other far right politicians, plutocrats also try to convince the public that they are pro-democracy.5 My view is that the system we live under is “Plutocracy with fascist characteristics”.

Though, simply saying that we live under plutocracy does not say anything about what the economic system is.

The economic system is often called neoliberalism, or free market capitalism. In theory, free market capitalism is where the economy is run by markets, with small levels of state intervention. The state’s legal focus is to protect private property rights. This is justified by the view that markets are a natural, self governing mechanism that allocate resources more efficiently than the state except for some minor imperfections.

In practice the neoliberal, or “free market” project has been to shape the state, markets, and legal system towards serving the rich, through central planning done by concentrated groups of private power.6 It has been shown many times over that free markets do not exist.

Not only that, but no one understands precisely what free market capitalism would be. To see this, consider that a century ago, free market fundamentalists used to argue that regulations against children working in coal mines was paternalistic intervention from the state.7 Likely very few self described free market fundamentalists argue in favour of that today.

In political science textbooks, liberal democracy is defined as when “people are seen as the best judges of their own interest”, and “everyone has an equal say in decisions which affect them”. I have argued that neither of these conditions are met under the current system.8 The textbook states the definition, but does not follow the conditions in order to demonstrate that we live in one.

The free market approach has been quite popular in the economics profession. It’s legacy can be found in the work of William Nordhaus. Nordhaus’s research argued that it was optimal to raise global temperatures by 3 or 4 degrees Celsius, because it would have very little effect on the economy, and had a GDP maximizing effect.9

Some of the research in this work contains lies so clearly deliberate that it would raise alarm bells for an average undergraduate.10 Several people did see the lies or “flawed methodology”, as nice academics call it, and have been criticizing it since 1983. This was the year in which an early report, co-written by physicists and economists, was shown to the Raegan administration. The economists perspective was given by Nordhaus and Thomas Schelling.

The physicist contributors' such as Alvin Weinberg were not nice in their assessment of the economic contributions, however. According to Weinberg, the report was “so seriously flawed in its underlying analysis and in its conclusions" with others saying that "we knew it was garbage so we just ignored it.”11

For the most part though, his work was fairly well received in environmental economics, or mildly criticized.12 Benjamin Franta is a historian who gives two examples of economists who dissented from the mainstream consensus. In a footnote, he names Martin Weitzman and Nicholas Stern.13

Nordhaus’s “optimal target” of over 3 degrees Celsius would likely get over a billion people killed,14 even with the knowledge that we had early on during the 4th IPCC report. Despite this, the dissenters that Franta mentions still expressed high regard for his work. For example, Martin Weitzman had this to say:

Bill Nordhaus, who more than anyone else founded the economics of climate change and has been a major contributor to the subject over many decades, is a balanced centrist pragmatic observer who avoids extremes of right or left (Weitzman, 2015).

Nicholas Stern has his own version of the history on free market approaches to climate change. His view seems to imply that Nordhaus couldn’t really know any better in the early 1990’s, because the science was not well known:

The IPCC was established, as a result of initiatives from scientists, in 1988, and climate change started to become a more active subject in discussions of policy. There was growing recognition that climate change could be disruptive, but at that time the common belief was that our emissions of greenhouse gases would cause only small perturbations at some point in the future. The modelling of climate change began with Bill Nordhaus’s important and admirable paper ‘To Slow or Not to Slow?’ (Stern, 2022).

The common belief in climate science and ExxonMobil by about 1979 was that climate change will be catastrophic15, not result in “small perturbations”, and that a catastrophe could be averted by phasing out fossil fuels, with renewable replacement.16

So what were the main criticisms coming from Weitzman and Nicholas Stern? To summarize, Weitzman argued that it’s too difficult to put a price on climate change due to the risk of catastrophic worst case scenarios. An analogy is that climate change should be treated like insurance. What is the insurance payout for civilizational destroying events? There isn’t one.

Nicholas Stern critiqued Nordhaus for using this thing called the “discount rate” and setting it too high. The discount rate fundamentally answers this question: "How much is $1 of benefit (or damage) next year worth in today's dollars?"

The discount argument on climate change was framed into the narrative:

“Because a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, we should not doing anything about climate change,17 because in 50 years time (which is in the year 2033), we will be so rich from pursuing GDP maximization that we will be able to pay for all the solutions for climate change.”18

It was previously used to say we shouldn’t do anything about acid raid either. This justification became a talking point for environmental delay in free market think tanks.19

In 2007, a report called the Stern Review was published. Stern argued for 1% of GDP devoted to public spending allocated for reducing emissions. Recently, he has increased these numbers up to 2-3%.20

Martin Weitzman argued for favouring a carbon tax, and perhaps funding research and development.21

The Centrist Approach to Climate Policy

I started this article by recognizing that the global population was the “centre” of opinion. As the Global South is about 80-90% of the worlds population, any majority opinion formulated in the Global South could be considered to be centrist.

In practice, the word “centrism” is not used to describe the opinions of the global population, or even national opinion. Rather, it’s used to describe elite opinion.22 We saw an example above of Weitzman, quite accurately describing the “centre” of opinion. But his meaning of “centre” was in fact restricted to the opinions of environmental economists working in elite universities.

So consider the centre as global opinion. The best formulation I know of represents the centre is the People’s Climate Agreement at Cochabamba in 2010. They argued for spending 6% of GDP per year on climate action:

Current funding directed toward developing countries for climate change and the proposal of the Copenhagen Accord are insignificant. In addition to Official Development Assistance and public sources, developed countries must commit to a new annual funding of at least 6% of GDP to tackle climate change in developing countries. This is viable considering that a similar amount is spent on national defense, and that 5 times more have been put forth to rescue failing banks and speculators, which raises serious questions about global priorities and political will. This funding should be direct and free of conditions, and should not interfere with the national sovereignty or self-determination of the most affected communities and groups.

This paragraph is in my view a better policy proposal than what any green growth or free market proposal has come up with, at least that I have seen. The reason I think it is better is because it’s democratic, unconditional, and would (if started in 2010), likely have prevented hundreds of millions of people dying. It also would have narrowed the divide between North and South.

It’s done in liberal way as well, because unconditional funding assumes that poor people are the best judges of their own interest. This is contrary to standard practices of loans to the South, which assume that third world peasants are too stupid to understand that free markets are good for them.

The free market and green growth economists put millions of hours of work into their policy proposals. Some good idea’s can be found there, but overall I think these third world peasants knew better, and probably didn’t put many hours of thought into the idea that 5% of GDP should flow to them. Perhaps that’s a good justification of the phrase “work smarter”, not “work harder”.

How Green Growth and Degrowth were Suppressed

Green growth and degrowth were marginalized from mainstream debate, but they have their roots in the 1970’s. The competing ideologies of green growth and degrowth will be explained in more detail later, but here are some preliminary definitions.

Definition of Green Growth

The term ‘green growth’ is widely used, especially by international institutions including the World Bank, the United Nations and OECD, and as of 2012, the Global Green Growth Institute. And yet, as Alex Bowen notes, there is no universally agreed definition of green growth, although ‘there is a broad consensus about what it means’ (Bowen, 2012). One widely used definition of green growth that seems to capture this consensus is that from the OECD: ‘Green growth means fostering economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies’ (Carlota Perez, 2019).

Definition of Degrowth

Degrowth is a planned reduction of energy and resource use designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human well-being (Hickel, 2021).

These definitions are pretty vague, even though they are the best that I can find. My own view is that most green growth scholars want to provide jobs for people while decarbonizing the environment at the same time. Degrowther’s want to do that as well, but in addition, they also want to scale down consumption and production at the same time.

How Green Growth was suppressed:

In my view there are two way’s that green growth was suppressed. One was due to pre-existing free market fundamentalism. The other was due to an international conspiracy, initiated by Total, the French fossil fuel company, in 1986.

As discussed above, Nordhaus did some of the earliest work on the economics of climate change, and had very strong influence over the entire subfield of environmental economics because of this, and his position at Yale university. The reason why thoughts of green growth couldn’t occur for William Nordhaus is as follows:

In the 1980’s, free market fundamentalism was so strong that most of the profession probably had a weaker understanding of how the economy works than the average person. There’s an example of this that Noam Chomsky gave in 1998. It involves Alan Greenspan naming 10 great innovations from the free market. About 9 of them actually originated or were heavily subsidized by the state.23

My general intuition here is that It took a long time for economics profession to become this indoctrinated. Free market fundamentalism goes back a long way24, and if the ideology is not exposed, then each new generation of economists inherits more dogma than the previous one. This does not happen in a linear fashion, but it does seem to be the general direction of economic thought over time.

For this reason, when Nordhaus started working on environmental economics, two axioms were a given for his analysis:

Axiom one: Everything can be analyzed through cost benefit analysis

Axiom two: A cost benefit analysis must prove that markets are the solution. Therefore the models in economics needs to make assumptions to argue for this conclusion.

This is the best explanation that I can think of that explains why Nordhaus’s model argued the environment is a trade off with GDP. To say that jobs can be created for sustainable development would necessitate state spending, which violates Axiom two. By Axiom one, we pigeonhole the analysis into a tradeoff between GDP and emissions.25

All of the assumptions after this point must justify Axiom two. Therefore, economic damages are calculated by comparing GDP to temperatures without consideration of time. Under this assumption, we can say that because Norway and Qatar have similar GDP per capita and a 10+ degree difference in average temperatures, we can extrapolate this kind of observation and say that raising global temperatures by 10 degrees Celsius won’t have too much of an effect on the economy.26

This is the kind analysis that Nordhaus and his students adopted. They also assumed that “about 87% in sectors that are negligibly affected by climate change” by climate change because it was indoors.27 It cannot be said that Nordhaus doesn’t have the brain to understand how ridiculous this statement is. In Climate Casino, he includes an entire chapter on tipping points, non-linearities, and discusses both climate and economic examples of this:

One of the most important lessons from the recent financial crises is that no one understood how fragile the system was. No one anticipated how profound the economic costs of the financial panics would be. We should heed this lesson as we think about the tipping points that might be crossed as we alter the climate (Nordhaus, 2013, p54).

Therefore he can understand that financial crisis can have ripple effects, such as reduced income in America putting manufacturers out of work in China. It should be far easier to understand that economic damage from climate change that affected people indoors would lead to loss of outcome from those who work outside.

Steve Keen is a critic who has compared this assumption to equating the climate with the weather.28 But it is clear that Nordhaus is intelligent enough to know the difference, but for whatever reason quite deliberately pretending not to.

Other assumptions were the discount rate. Putting this together, Nordhaus likely had the effect of leading a subfield astray. Combine that with the fact that some of his students were in fact corporate shills, you can see how an echo-chamber would be reinforced.29

Here are some of the results of this echo-chamber. From 1990-2020, there were about 6000 estimates of the social cost of carbon, which is defined as the “cost to society that releasing one ton of co2 into the atmosphere has.”30 These social cost of carbon estimates were used to justify what the price of a carbon tax should be.

Such estimates were usually between $10-$100. By 2020, they were averaging about $100-300. Now they are pushing into the thousands.31 Nordhaus himself estimated it to be $31.32 In New Zealand our Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton, argued for a $10 carbon tax in the early 1990s. The farmers went ballistic at such a high price.33

Fossil Fuel Companies Unite against Green Growth

In the late 1980’s, creating environmentally useful jobs was starting to become a popular idea. It was called sustainable development rather than green growth. Here it explicitly stated in a highly cited report on this discussion in 1987:34

These links between poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation formed a major theme in our analysis and recommendations. What is needed now is a new era of economic growth - growth that is forceful and at the same time socially and environmentally sustainable

Another popular academic work to come out in 1989 was Blueprint for a Green Economy. This also wrestled with green growth and sustainable development:

A society which does not maintain or improve its real income per capita is unlikely to be “developing”. But if it achieves growth at the expense of the other components of development it cannot be said to be developing either. Achieving economic development without sacrificing an acceptable rate of economic growth may be said to define the problem of sustainable development .… For the moment we observe that growth does not necessarily involve environmental degradation. (Pearce et al., 1989, p. 30).

The fossil fuel industry at this point was monitoring and tracking the scientific literature in order to create an early response, and so would likely have been well aware of this. Here the response seems to have been to suppress green growth ideas by killing them at birth. An international conspiracy initiated by Total, the French fossil fuel company, set out to accomplish this task. By 1990, hundreds of oil companies were communicating denial strategies together.35

In early 1986, Tramier sent a report to Elf’s executive committee, in which he described global warming as certain to occur and a key issue requiring a defensive strategy by the industry, writing:

“The problems related to the interactions of various pollutants in the upper atmosphere will become of concern in the coming years. … All models are unanimous in predicting global warming, but the magnitude of the phenomenon remains undetermined. The first reactions were, of course, to 'tax fossil fuels', so it is obvious that the oil industry will once again have to prepare to defend itself.”

Tramier’s report was included in the minute of Elf’s executive committee meeting of March 4, 1986, found in Total’s corporate archives in Paris (p138, Franta, 2022).

Because providing both jobs and sustainability goals does not have a cost, I argue that this quote displays the key strategy for green growth denial:

To defeat public policies that could “shift ... the energy resource mix” away from fossil fuels or “even [require] abandoning resources,” LeVine explained that the industry should emphasize uncertainties in climate science and the costs of fossil fuel controls, call for further research, and promote industry-friendly alternative policies that would keep the fossil fuel business intact (p138, Franta, 2022).

But you could also see the above quote as being aware of potential degrowth proposals for reducing production. In any case, this was followed up with:

The API and its allies were following the strategy set out by Exxon’s Duane LeVine in 1989, promoting the notion that climate science was uncertain and even denying basic findings such as the fact that CO2 would amplify the greenhouse effect. Another prong of LeVine’s strategy, however, was to portray fossil fuel controls as prohibitively costly, and the API went to work on this as well, commissioning a report in 1991 from economic consultant David Montgomery, who warned that reducing carbon dioxide emissions even by modest amounts would shrink the U.S. economy by 2.4% by the year 2100 (p153, Franta, 2022).

The economy vs environment narrative is much the same as jobs vs environment:

According to Charles River Associates, an economics research organization also doing studies on this issue, a mandate to stabilize carbon dioxide emissions at or below current levels in the United States could require a new tax of $200 a ton of carbon burned ... This could mean a 2 percent drop in our gross national product in the last half of the 1990's, resulting in a drastic impact on jobs, as well as on our standard of living. We are facing the equivalent of a $100 billion tax on Americans without solid scientific evidence(p191, Franta, 2022).

Thus kind of propaganda is still pushed on the right wing media, and consulting companies today. It seems to have dominated for a full two decades.

But it also allowed the fossil fuel industry an additional pathway to combat climate scientist’s in the so called marketplace of ideas. They could appeal to arguments that were outside of their field of expertise. In order for scientists to win an argument, they now had to know everything.

How Degrowth was suppressed:

Many people in my own generation seem to have a problem with boomers. However, the fact is that the environmental activism could be considered one of the biggest achievements for the boomers who were involved as young adults.

In particular, degrowth ideology could be argued to originate around 1968-1972.36 In 1968 was when student activism blew up. In 1971, the field of ecological economics was founded by the economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen. This incorporated energy into economics, and centered the economy as part of the ecosystem, rather than being separated from it. Then in 1972, The Limits to Growth (LTG) was published. Heard of this book? It was one of the most influential books of the 20th century, and sold over 30 million copies. According to the people who worked on this, virtually no one understands what it’s about anymore.

Ugo Bardi gives an accounting of what the LTG was actually about, and how it came to be suppressed:

The core message that was contained in LTG, and reinforced in two later versions, most recently in 2004, was that in a finite world, material consumption and pollution cannot continue to grow forever. When LTG was published, it created a widespread discussion which quickly turned from a scientific debate into a political one, driven by ideology and special interests. Despite often being depicted as such, none of the LTG studies were a prediction of unavoidable doom. Rather, LTG “pleaded for profound proactive, societal innovation through technological, cultural and institutional change, in order to avoid an increase in the ecological footprint of humanity beyond the carrying capacity of the planet.”

Bardi goes on to explain the scientific and public perception of LTG over time:

The publication of “The Limits to Growth” in 1972 had a very strong impact on the public opinion; so much that some feared it would spread out of control. For instance, K.R.L. Pavitt wrote about LTG: “.... neo-Malthusians are bound to increase in numbers and to be right about the end of economic growth sometime in the future. In the industrially advanced countries, this should be relatively soon” (Cole et al. 1973, p. 155).

That did not happen, of course. Instead, in the late 1980s and 1990s the world witnessed a rejection of the LTG study so complete and pervasive that it is surprising for us to discover quotes such as this one.

With the 1990s, it became politically incorrect even to mention the LTG study, unless it was to state that it was wrong or had been discredited. Only in recent times a reappraisal of the LTG study seems to be in progress, but the negative attitude is still widespread and probably prevalent. The question, therefore, is how a work that was initially hailed by some as a world-changing scientific revolution ended up being completely rejected and even ridiculed.

Here again, the culprit appears to be the economics profession. The LTG was sharply criticized by William Nordhaus. According to Bardi, he seems to have not understood the science behind system dynamics, nor cared to:

Nordhaus is simply looking at one of the several equations of the model without realizing that the output of each equation will be modified by the interaction with all the other equations and that will insure correct returns to scale. This is the essence of systems thinking: that parts interact.

Paul Krugman reports how he and his research advisor of the time, William Nordhaus, reacted to the publication of Jay Forrester’s “World Dynamics” in 1971:

The essential story there was one of hard-science arrogance: Forrester, an eminent professor of engineering, decided to try his hand at economics, and basically said, “I’m going to do economics with equations! And run them on a computer! I’m sure those stupid economists have never thought of that!” And he didn’t walk over to the east side of campus to ask whether, in fact, any economists ever had thought of that, and what they had learned (Krugman 2008).

Bardi also notes that the economics journals did not publish any rejoinders to Nordhaus’s critiques, contrary to standard practice in the sciences.

The criticism of Limits to Growth eventually became completely hysterical, involving denunciations of the scientists behind it as plotting for world domination, and/or extermination from the darker races. A bit of guilt by association with Malthusian eugenics was thrown in there too.37 These conspiracies were based off fabrications and/or cherry picked data, and pushed by both free market fundamentalists38, Marxists and even other scientists.39

The Limits to Growth has been reviewed again recently. Degrowther’s write that:

Previous studies have explored how the various runs of the Limits to Growth model compare with actual trends and suggest that the world is most closely tracking the Double Resources scenario, which differs from the Standard Run in its assumption that the initial stock of non-renewable resources is twice as large as the Standard Run resource stock.

In this scenario, collapse occurs later and is driven not by scarcity of non-renewable resources (ie, a source limit), as in the Standard Run, but by persistent pollution and its impact on ecosystem stability (ie, a sink limit, otherwise known as a regenerative capacity limit). The Double Resources scenario arguably aligns more closely with the current understanding of the most pressing environmental limits facing humanity (Kallis et al., 2025).

In conclusion, criticism of The Limits to Growth largely went from soft criticism from other scientists, to ignorant criticism from economists who didn’t understand system dynamics. Then onto fabrications and cherrypicked tables arguing that it was based on [nonexistent] predictions that the world will collapse by the 1990’s. Then onto denunciations of scientists having a secret agenda of planning world domination and mass genocide.

Bardi compare’s it to the standard strategies from the Merchants of Doubt who denounced Rachel Carson as “killing more than the Nazis” for the crime of exposing the deadly dangers of pesticides. However, he does not quite find absolute proof of a link to free market think tanks, as has been done for other industries.

Suppressing the Green New Deal

There is also the Green New Deal (GND), which I have found to be proposed as early as 1983. The GND proposal is to increase public spending, say by 2-5% of GDP. Both green growther’s and degrowther’s have largely supported the GND.40 This is because both agree that a large increase in the use of public money is required for any solution.

An Overview of the Similarities and Differences

The similarities and differences between green growth and degrowth have already been written about by Jonathan Boston, a professor on public policy has done the exact same thing.

On the policy similarities, I largely agree with both ideologies. On the differences, I favour degrowth. On the differences in political and moral views, I also favour the degrowther’s. On the differences of strategy for achieving their goals, I strongly favour the degrowther’s.

That said, I will note the disagreements I have with each ideology as I compare them, one by one.

1 Agreements and Disagreements

Generally, I think all policy proposals from green growth scholars are supported by most degrowth scholars. However, degrowth wish to massively curb consumption and production on top of what green growther’s are proposing.

The problem with comparing agreements and disagreements between these two ideologies, is that every single scholar also has their own points of view. There’s a spectrum of thought. You can find degrowther’s that think it’s possible to have infinite real GDP growth on a finite planet. You can find green growther’s that want to reduce consumption and production.

It’s not possible to read everyone’s work, so the best way to go is to look at what the most cited scholars in each field say:

Degrowth scholars include:

Green Growth scholars include:

Joseph Stiglitz, Nicholas Stern, Sam Fankhauser, Paul Krugman

I’ve also included points from Green New Deal advocate Robert Pollin, and a few others that critique degrowth, such as Branko Milanovic, Ezra Klein’s critique in Abundance. There’s also handbooks for both degrowth and green growth.

What do they agree on?

Using quotes from scholars in each field, I argue that they agree on the following:

(1) Production and consumption should discriminate for low carbon intensive activity, and against high carbon intensive activity.

Degrowth has a discriminating approach to reducing economic activity. It seeks to scale down ecologically destructive and socially less necessary production (i.e. the production of SUVs, arms, beef, private transportation, advertising and planned obsolescence), while expanding socially important sectors like healthcare, education, care and conviviality ( Hickel, 2020).

That said, while it’s possible to decouple growth from environmental harm, that’s not automatic. To combine rising living standards with an improving environment, we need policies that encourage the use of technologies that cause less environmental damage (Krugman, 2023).

(2) We shouldn’t be concerned with gross domestic product (GDP).

In addition to rejecting the tenets of neoliberal globalization, post-development thought also rejects the notion (introduced by colonizers and international financial institutions) that GDP growth should be pursued for its own sake, preferring instead a focus on human well-being ( Hickel, 2020).

In short, what is relevant is not growth in GDP but growth in a multidimensional measure of well-being, and with climate change increasing apace, it should be clear that there may be marked differences between the two (Stiglitz & Stern, 2023).

(3) Increasing investment in research and development, with emphasis on technological gains and energy efficiency improvements, and expanding solar and wind.

Degrowth seeks to expand universal public goods and services, such as health, education, transportation and housing, in order to decommodify the foundational goods that people need in order to lead flourishing lives …

Degrowth is part of a plan to achieve a rapid transition to renewable energy, restore soils and biodiversity, and reverse ecological breakdown (Hickel, 2020).

There are powerful increasing returns to scale in both production and discovery for new technologies arising from scale technologies, learning by doing, and induced innovation. This means that as we shift more to the green economy, costs may fall—and growth will increase. These are reflected in part in the rapidly falling costs of production of solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries (Stiglitz & Stern, 2023).

(5) Reducing wealth inequality.

Degrowth seeks to reduce inequality and share national and global income more fairly, such as with progressive taxation and living wage policies (Hickel, 2020).

There are still other taxes that might simultaneously improve economic performance or enhance social justice: other environmental taxes, various forms of financial taxes, real estate taxes, and inheritance taxes (Stiglitz & Stern, 2023).

(6) carbon emissions can be reduced while GDP increases. This is also known as absolute decoupling.

Over the past decade, some countries have reduced their CO2 emissions while increasing their gross domestic product (Hickel &Vogel, 2023).

But at higher levels of development, delinking growth from environmental impact isn’t just possible in principle but something that happens a lot in practice (Krugman, 2023).

Disagreements:

(1) Political views on capitalism, exploitation, just transition, and growthism.

Degrowther’s argue that capitalism is undemocratic, exploits the Global South. In turn, they also argue that the Global North and rich people are responsible for the vast majority of the climate crisis, and so owe an ecological debt to the Global South.

Impossible to cover everything here. The book “The Future is Degrowth” covers all the main political views from degrowther’s. There’s also a lot of discussion on conviviality, which can be achieved by decommodifying a lot of work but also by expansion of commoning, which refers to the collective practices of managing and reproducing resources. This could reduce consumption through shared use of resources, and decrease social atomization

Green growther’s like Krugman and Stiglitz want a much nicer capitalism. Stiglitz argues that “neoliberal capitalism”, which is the version we had for the last 5 decades, is undemocratic and has contributed to the rise of fascism.

Most economists these days do not use the word capitalism in their textbooks or research. They argue that it’s used for political rhetoric. This may be true, but it’s a bit selective. So is virtually every other political word that they and everyone else use on a daily basis. In any case, I don’t yet have much to go off for political views of green growther’s.

It is common in Western discourse to claim there is a natural connection between capitalism and democracy. Sometimes the two concepts are virtually fused together. I always find this odd because I value democracy, but there is nothing democratic about capitalism….

Under capitalism, production is controlled overwhelmingly by capital: the big financial firms, the large corporations, and the 1% who own the majority of investible assets. They are the ones who determine what to produce, how to use our collective labour and our planet’s resources, and what to do with the surplus we generate (Hickel, 2025).

Exploits the Global South

They also argue that since the start of European expansion in the fifteenth century, growth in the centres has been based on (neo-)colonial appropriation, extractivist exploitation of nature, and the externalization of social and ecological costs. Thus, countries in the South were reduced to the dependent role of raw material suppliers without large value-added contributions of their own, causing ever-deepening inequalities and unequal power relations. And this critique argues that these processes of appropriation and externalization are fundamental to the growth dynamics of rich societies, the balance of power within them, and the stability of the imperial mode of living. In the context of increasing ecological crises, this way of life causes systemic crises because it cannot be generalized (Schmelzer et al., 2022, p. 96).

The safe planetary boundary for CO2 emissions is 350ppm, which was exceeded in 1988. Not all countries are equally responsible for this overshoot, however. Some countries have exceeded their fair share of the safe boundary, while others have not…

It is important to note that, while emissions are normally calculated at the national level, these figures obscure significant class inequalities within countries. Responsibility for excess emissions ultimately belongs to the wealthy classes who have high lifestyle emissions, who disproportionately control the system of production and distribution, and who wield disproportionate power over national policy (Hickel, 2025).

Growthism

When the OECD was founded in 1960, the top goal in its charter was (and remains) to ‘promote policies designed to achieve the highest sustainable rate of economic growth’. Suddenly the objective was to pursue not just higher levels of output for some specific purpose, but the highest rate, indefinitely, for its own sake….This new focus on GDP growth for its own sake – growthism – forever changed the way that Western governments managed their economies (Hickel, 2020).

My view:

The word capitalism has lost all meaning in public discourse. I view it as being defined as an:

Economic system where private individuals or businesses own the means of production and make decisions about what to produce, how to produce it, and for whom, primarily motivated by profit.

Whatever version of capitalism that may have existed in the last 600 years, I cannot see any of them meeting the conditions of “liberal democracy” as stated in the political science textbooks. So I agree that capitalism is undemocratic in all forms that have existed.

I don’t see any reason to debate that the Global South is exploited by the Global North. There are clear power dynamics there, so I agree with that.

Hickel’s argument for moral responsibility leads to a fairly similar outcome to mine. But differs in it’s reasoning somewhat. He argues that responsibility can be attributed to cumulative emissions starting in 1850.

I don’t agree that any nation should be responsible for emissions created before 1896, which was when global warming was discovered. Responsibility for Climate Change in my view begins at around 1959, when Edward Teller warned the American Petroleum Institute of the consequences.

The reason’s for this is that harm done without any reasonable ability to know that it could occur is not something people get put in prison for. So it shouldn’t apply to nations that caused emissions before this time.

I reject the concept of paying for reparations. My view is pretty simple. The more powerful you are, the more responsible for societies woes. Doesn’t matter what your society did in the past. This tracks similar to Hickel’s inequality based argument for responsibility.

In general, I end up having a pretty similar view to Hickel. Two policies that could very easily be implemented to curb exploitation of the Global South right now would be a debt jubilee, and not evading taxes (mis-transfer-pricing). That would likely generate well over a trillion dollars a year in wealth for the Global South. Though it wouldn’t go far enough, a debt jubilee requires only a single decision to be made.

I disagree with Hickel’s understanding of capitalism as being motivated by growthism defined as GDP maximization.

Consider the following two examples:

A system with high wealth inequality will result in lower consumption (and therefore production), because rich people tend to not consume much of their wealth. They put it in tax havens. So the statistic of GDP goes down.

The second thing is that the profit motive has led to a financial system that does not care about investment that boosts GDP. Share buybacks, and real estate bubbles are what finance has been chasing. This surely is bad for GDP growth. There’s also GDP reduction from global warming, financial instability, and unnecessary unemployment.

Executives do not sit down together and talk about how to maximize GDP. If they do, it’s because they are full of shit. Presumably they are motivated by wealth, power, status, and similar sociopathic goals. A profit motive gets you all of that. So I mean yes, millions of commenters out there constantly discuss GDP, millions of times, as if it’s a driving force in the economy. All of those people are wrong.

It could be argued that GDP is a useful statistic for degrowther’s, simply because it can be used to measure how resource and energy use relates to production. That’s a big part of what ecological economics is about.

As for well-being, it seems pretty hard to argue against:

Well-being is a multifaceted construct and while there is no consensus on a single definition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes well-being as “the presence of positive emotions and moods, the absence of negative emotions, satisfaction with life, fulfillment, and positive functioning”

I’ve never met anyone tell me that they want an unsatisfying life. A few negative emotions are needed now and again, but overall, I don’t see anyone can oppose well-being.

In general, I agree with degrowther’s on most of their politics, except their understanding of capitalist growthism as GDP maximization. This is clearly wrong.

(2) The probable effect on GDP as a result of their policies

Degrowth, similarly to steady-state economics, regards a lower GDP as a probable outcome of efforts to substantially reduce resource use (Kallis et al, 2025).

Humans are risk-averse—they are willing to pay a lot to avoid risk and willing to pay an enormous amount to avoid extreme risks such as those associated with climate change, reinforcing the conclusion that the presence of risk implies that stronger climate action is desirable. And taking these stronger actions will result in a higher growth in risk-adjusted expected GDP (Stiglitz & Stern).

My view:

I think that if society tried really hard to offset waste as much as possible, then GDP will go down in aggregate. The position from green growth probably stems from underestimating the amount of waste under capitalism. They do not think very much about consumerism, planned obsolescence, military spending, and other GDP waste that would be gotten rid of. Some of them would surely disagree with degrowther’s on what constitutes waste.

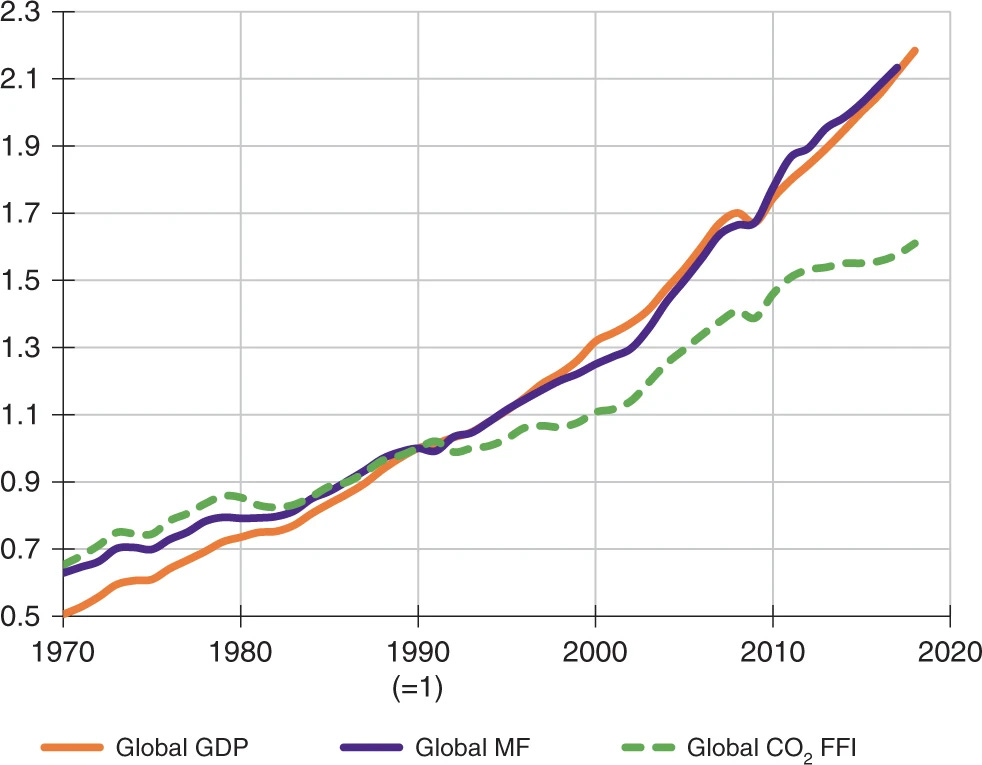

(3) The level of decoupling between GDP and emissions that can be accomplished by green growth

The emission reductions that high-income countries achieved through absolute decoupling fall far short of Paris-compliant rates. At the achieved rates, these countries would on average take more than 220 years to reduce their emissions by 95%, emitting 27 times their remaining 1·5°C fair-shares in the process. To meet their 1·5°C fair-shares alongside continued economic growth, decoupling rates would on average need to increase by a factor of ten by 2025 (Vogel & Hickel, 2023).

My view:

I didn’t look too hard at the math here, but it seems reasonable from all that I’ve seen. I would also note that these are projections given by really existing policies. Stiglitz and Stern pathways would likely go a lot further in absolute decoupling. But still not enough, and not nearly as much as they should, from a moral point of view.

What actually needs to happen (as of 2022):

We’ve pretty much missed this much steeper decoupling target of 1.5 degrees. Regardless, basic moral intuitions say that doing more for the environment is morally better than doing less.

(4) Emphasis on how big of a problem Energy and Material footprint is wildly different.

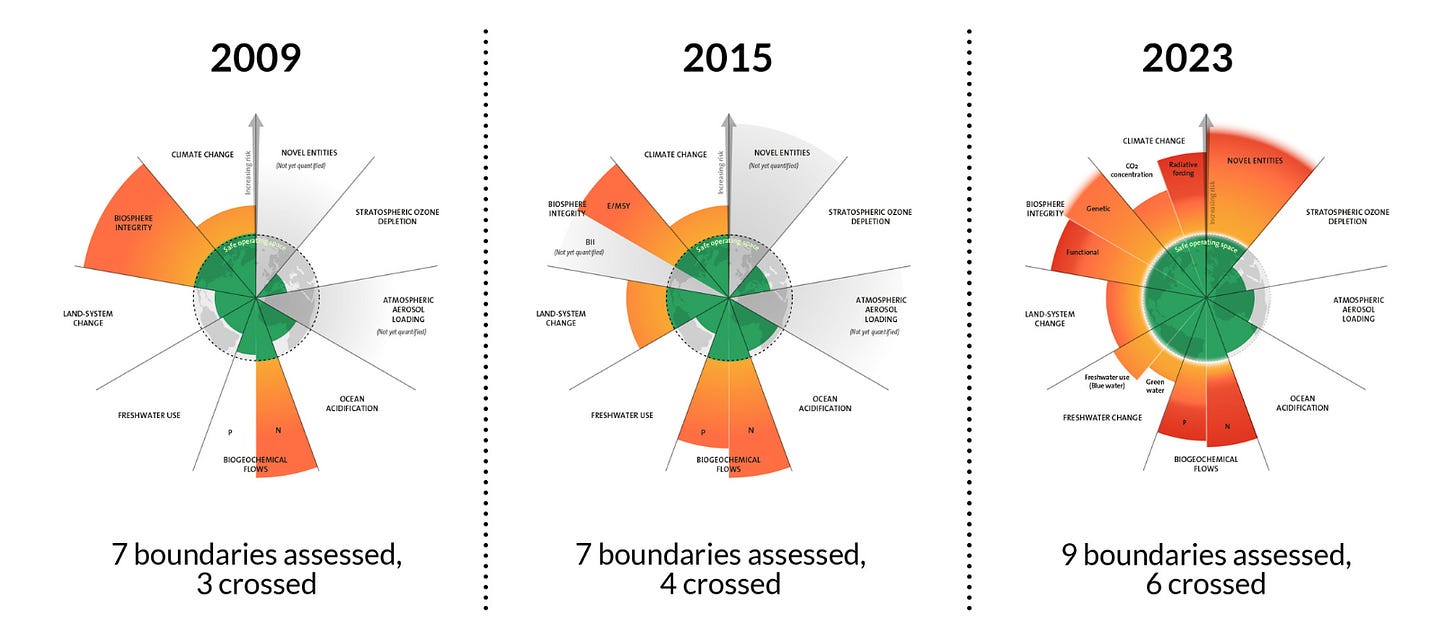

Global material use has increased markedly over the past half century, to the point where, as of 2017, the world economy is consuming over 90 billion tonnes of materials per year—well in excess of what industrial ecologists consider to be the sustainable limit. This increasing trend holds across all categories of materials, including biomass, metals, non-metallic minerals, and fossil fuels….

However, the boundary is somewhere, and it is clear that it has already been exceeded. Industrial ecologists have proposed that a sustainable boundary for global resource use might be around 50 billion tonnes per year. Global resource use exceeded this level in 1997. This level is generally considered to be an upper limit boundary; Bringezu proposes a target sustainability corridor of about 25–50 billion tonnes per year (Gt/a). Global resource use exceeded 25 Gt/a in 1970 (Hickel et al, 2022).

Planetary boundaries do impose constraints (Rockstrom et al., 2009). In the next two or three decades, climate action is likely to help in addressing these problems. In the later part of the century and moving into the next, the boundaries may well constrain growth (both in GDP and population) and should already be prominent in thinking about public policy (Stiglitz & Stern, 2023).

My view:

I picked out these two quotes to show how different the perceptions are when it comes to the current ecological crisis we are in. Stiglitz and Stern seem divorced from reality here, because they are about half a century off in their estimate for the time window. This perspective is quite common among the green growther’s from what I’ve seen.

Material footprint is defined as the total amount of raw materials extracted from the environment to satisfy the global economy's final consumption demands. It’s now well over 100 billion tons. That’s twice over the safe limit for planetary boundaries. Based off this simple observation, it would be more correct to say that the time window ended in the late 20th century than it is to say that we should worry about it in the 21st century.

Hopefully, we can see why the degrowther’s are heavily in favour of reducing consumption and production now.

(5) Is infinite growth on a finite planet possible?

The claim of whether infinite growth on a finite planet is possible cant be known until we define what growth is. Two definitions of growth give two different answers:

(A) If growth is defined as real GDP, then you can probably have infinite real GDP growth on a finite planet.

(B) If growth is defined as material footprint, or energy footprint, then you can obviously not have infinite growth on a finite planet.

Claim A:

Because humans are infinitely creative, there can likely be infinite energy efficiency improvements. However, we have had energy use outstripping the energy efficiency improvements over time. Which is unsustainable. If rates of energy use > energy efficiency improvements over time, then the earth will eventually be cooked.

Some goods are already operating at near peak efficiency, and so those efficiency gains have to come from new goods or services. Therefore only some of our GDP has energy efficiency improvements. These improvements have to come from other goods and services.

Here I want to define two concepts in the post growth literature.

Definition: Relative decoupling is when economic growth outpaces the growth of resource use or environmental damage, even if the latter is still increasing

Definition: Absolute decoupling means that as an economy grows, the overall consumption of resources and/or the environmental impact (e.g., emissions) decreases in absolute terms, rather than just growing at a slower rate.

In the book “The Future is Degrowth”, the scholars claim that:

There are some signs of global relative decoupling and of some regional absolute decoupling. For example, the global energy intensity (amount of energy per unit of global GDP) today is almost 25 per cent below that of 1980, and the carbon intensity of the global economy (amount of CO2 per unit of global GDP) has also declined by almost 1 per cent per year in recent decades

In summary, it seems to me that as GDP growth strongly correlates to energy use, and because energy use is larger than energy efficiency improvements, then GDP growth is unsustainable at high levels. However, if GDP growth was around 0.5% a year every year since 1900, then we would be probably be using less energy now than we were back then. So if GDP growth was very low, we would most likely be able to have infinite GDP growth.

Claim B:

The answer is obvious in accordance to the laws of thermodynamics. No explanation is needed to see why you cannot keep using more and more energy on planet earth.

Jevons Paradox

An often cited idea from degrowther’s is what’s called the Jevons paradox. This paradox says that even when a technology becomes more efficient, you will get a rebound effect. Which means more resources will be used even though energy efficiency improvements were made.

A recent example of Jevon's paradox is Artificial Intelligence. The large language models have become far more efficient over the last 5 years. But they have also become over a 1000 times larger, with ever increasing expansion of data centres around the world to run them.

This example is not isolated. In aggregate, Jevon's paradox has basically held true since it was discovered. Energy efficiency improves, but energy use always grows faster. The overall effect is exponential growth in energy use. If that continues, we end up cooking ourselves.

In this section we saw what green growth and degrowther’s agreed and disagreed on.

The biggest differences are their estimates for how big of a problem that growth of material and energy use it, and the level of emphasis on politics, philosophy, and justice.

The next section takes a deeper look at the policy proposals from green growth and degrowth advocates.

Policy Pathways:

There are several ways that degrowther’s advocate reducing consumption and production. My favourites are sharply reducing advertising and planned obsolescence.

According to a marketing consultant Victor Lebow, the goal of consumerism is to encourage waste maximization, and force it on people:

We require not only “forced draft” consumption, but “expensive” consumption as well. We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing pace (Lebow, 1955).

There was a lot of discussion on how to produce as much waste as possible in the 1950’s, because people were not buying enough. Since then, this has become much worse. This is important to point out, because many people seem to think that drastically reducing consumption would lower people’s quality of life, and hence associate degrowth with austerity.

One way of trying to argue over whether advertising is justified is to argue about it’s mental health effects. These kinds of debates are studied for the recent commentary on overuse of smart phones for example.

A much better approach, in my view, is to simply use philosophy and look at the justifications for this industry that are given by the industry itself. Then ask whether they hold up?

A moral justification for manipulating children into nagging their parents to buy things was given by Peter Reynolds, then CEO of a toy company:

"Parents aren't losing control, they're giving it up, …If your child nags you to let him play in the middle of the freeway, do you do that? The responsibility of the purchase always lies with the adult. Yeah, 72 times a day you're going to be asked: Can I have that toy? Can I have that toy?' But if the answer is no 72 times a day for three or four weeks, then they stop asking." (Linn, 2004)

The argument seems to be that if you don’t tell your kids that they are not allowed a toy times 72*7*4 = 2016 times, then you have shitty parenting skills. It happens to be the case that single parents, poor parents, and two full time job parenting families are in fact the “shittiest”, because marketers figured out that these ones have the hardest time saying no to the nag.

Other argument’s I’ve seen are “my kids turned out fine”, and “I’m just doing my job”, and “we are providing the right for kids to be consumers, and getting them to consume is a privilege” (James McNeil’s argument). Though some people in the industry argue that their developmental psychology degree is being used for evil purposes, and seem to hate their job and think it’s terrible for society.

Degrowther’s aim to improve people’s lives and reduce environmental harm by reducing or eliminating forced consumerism. The inventor of child targeted advertising is a guy called James McNeil. He spent his whole life figuring out how to get kids to consume. He thinks you can get about $100,000 from a person over their lifetime, if you advertise to them at as young as six weeks old.

James McNeal, a psychologist who has written extensively about how and why companies should market to children, estimates that a lifetime customer could be worth $100,000 to an individual retailer. Babies are a once and future gold mine for marketers, which helps explain why companies such as Ralph Lauren and Harley Davidson are now targeting infants and toddlers by putting out items like tiny T-shirts and sweatshirts with their logos on them. (Linn, 2004)

This industry of forced consumerism by his estimate, would accumulate to single digit trillions if you count it all up (and take inflation into account).

There are also externalities like obesity, mental health, increased materialistic values, unnecessary industries devoted to recycling and waste colonialism (dumping garbage in poor nations), and likely a loss of creativity and individualism.41

Gen Z is the first generation to be indoctrinated with consumerism from the moment they are born, as they are young enough to have watched Teletubbies as an infant. That show was supposedly the first TV show that was marketed towards under 2 year olds. Now, simply by being born in any major city, you are making money for Jeff Bezos by existing. Your existence is monitored and studied by the Internet of Things, which is the set of all electronic devices that surveil you.

On the production side, degrowther’s argue in favour of banning planned obsolescence, and ensuring the right to repair. Planned obsolescence is the practice of making products intentionally break earlier, so people have to buy them more. One famous example of this is the Phoebes cartel, which produced lightbulbs at half their previous life expectancy.

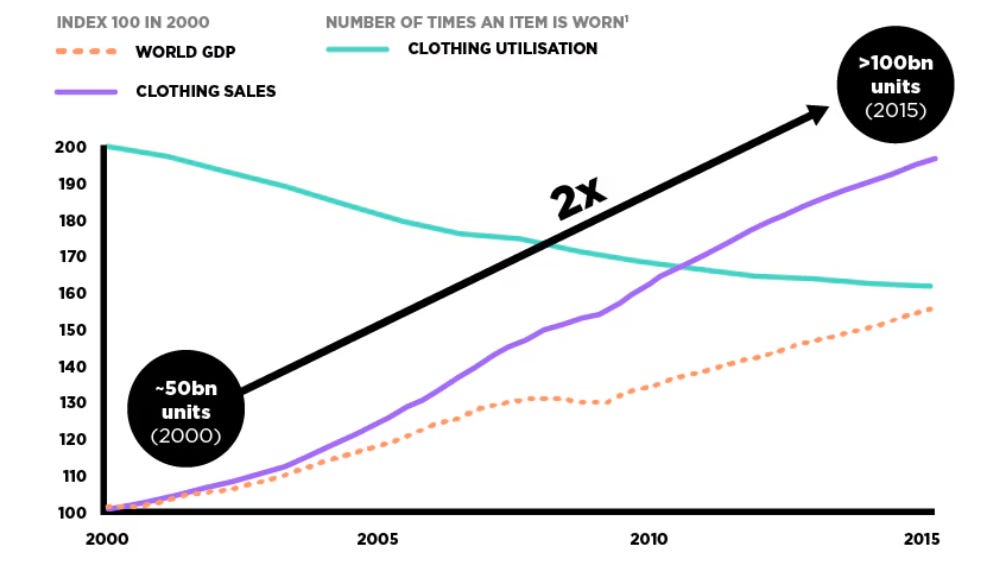

Planned obsolescence can come in many forms. Consumerism for example has exploited “psychological obsolescence”, which is the generation of increasingly rapid loss of desire for products. This is where seasonal fashion comes from. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French finance minister helped develop seasonal fashion under King Louise the XIV. Originally it was two seasons a year. The fast fashion industry developed in the 1990’s and quickly expanded this to 52 micro-seasons per year

The fast fashion industry was taken over by the ultra-fast fashion industry during Covid. In this new development, the seasons are largely determined by machine learning algorithms, and influencers on TikTok or Instagram . The algorithms figure out niche interests people have and create the clothes that will go out of interest very quickly, to keep them (mostly young women) buying more. As a result, the effect of psychological obsolescence here can actually be graphed.

The ultra-fast fashion industry also contributes towards astronomical (not hyperbolic) levels of environmental and social alienation. Including microplastic pollution, water pollution, water scarcity, waste colonialism, wage slavery, knowledge theft, shopping addiction, and suppressed innovation.

Degrowther’s also argue for reducing the work day, and I think in this industry that would work well with combined reductions in advertising and waste maxing.

There is also a third industry called “slow fashion”. This industry puts the creator above the consumer, and has actually grown in the Global North in recent years. It’s fairly niche but offers an example of creative, fulfilling, high quality production that society could work towards. The same could be said for engineers who make washing machines intended to break, or software engineers that make software intended to slow down.

Recent developments in planned obsolescence have been the deliberate blocking of reparability. This exists for AI-based industrial agriculture (tractors that cannot be fixed because the code to use them is on the cloud, or locked beyond an access code). I-phones and car manufacturers use all sorts of tactics here. The fast-tech industry is growing and there will likely be more examples of “cloud obsolescence” because of this. This kind of obsolescence makes it impossible for people to repair gadgets if their code/functioning ability is located on the cloud.

Planned obsolescence gets a brief mention in the green growth handbook:

It is now widely recognised that there are simply not enough resources on the planet – raw materials, water, air, land – to support it…. The ‘good life’ is visibly shifting from heterogeneity to custom – and viewed from the supply side, from the mass consumer to a plurality of consumers and from wasteful ‘planned obsolescence’ to truly durable products that can move from hand to hand maintained in good condition ( Carlota Perez, 2019).

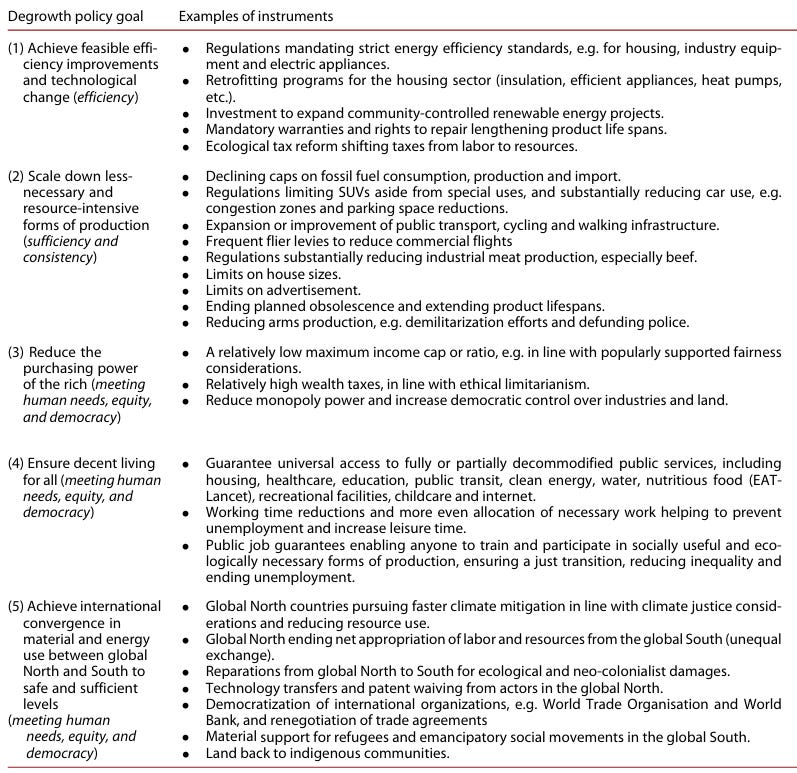

So, getting rid of advertising and planned obsolescence are the two favourites of mine. What else do degrowther’s propose? Pretty much everything, actually. Here’s one paper that gives examples of other idea’s that they are in favour of:

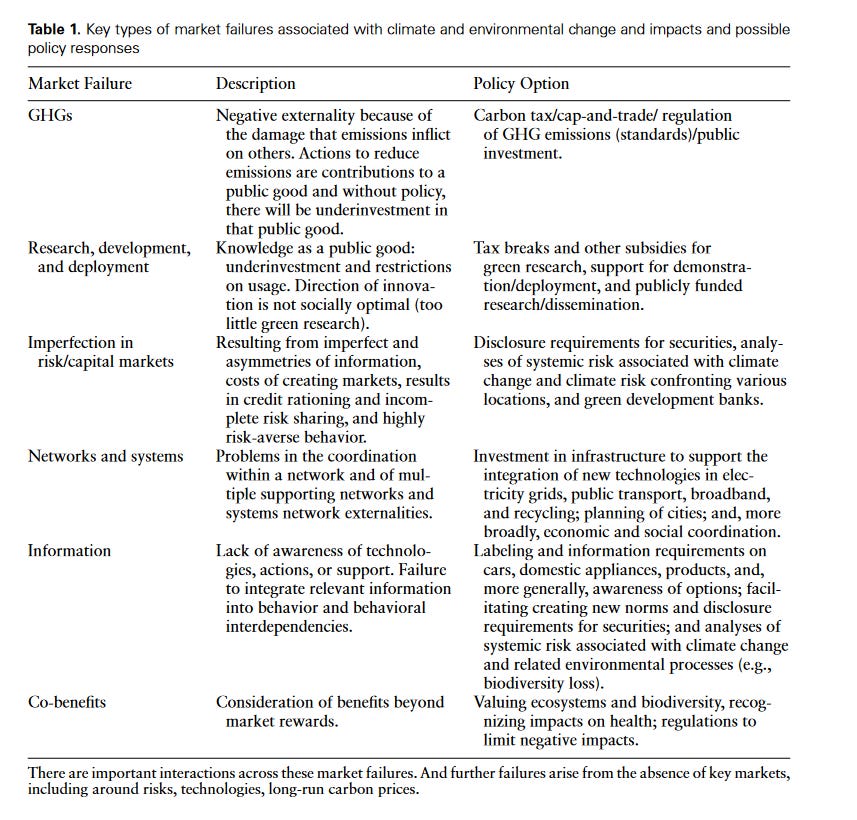

The green growth pathways also want to throw in a lot of policies. The following table is one that I’ve taken from Stiglitz and Stern.

Comparing the two tables gives a pretty good overview of the differences. There’s a lot of overlap, but green growth is minimal in decreasing consumption, production, and extravagance. Degrowther’s do not have the “nudging” ideas from behavioral economics that Stern and Stiglitz advocate.

Degrowther’s also argue that there need to be reductions in house size, and luxury products that have significant environmental externalities. Like flying, beef consumption, SUV’s, and such. The emphasis here is on rich people, and middle income in the global north having to cut down on excess consumption. Some of it’s forced, some not. While at the same time, degrowther’s have argued that poverty can and should be eliminated in the Global South (and Global North). This is an honourable and morally just position to take.

They also argue in favour of macroeconomic policies like Universal Basic Income, the Job Guarantee (anyone who wants a job can easily get one), and Universal Basic Services (publicly paid utilities, transport, education, health). There’s debate going on here. I think all three should and can be supported.

One objection to having all three is that it would be “too expensive”. This objection is usually based in the mistaken belief that money, instead of resources (labour, energy, capital, the ecosystem) are the constraints on public spending. These people (such as Stiglitz and Stern) believe that tax revenue is required to pay for all of this. It isn’t, because you can use the central bank to create credit. Tax revenue is a return on money that’s already been created. The word “revenue” has French etymology. It means “to return”.

Some green growther’s would agree with my position on taxes and credit creation here instead of Stiglitz and Stern. Most degrowther’s agree with me.

Jason Hickel has also argued in favour of industrial policy that has a discriminatory approach to finance. This is called “credit guidance”, and was used in South Korea and other nations in order to support the long term development of certain industries.

The goal is to force banks to provide cheaper credit for particular industries (like regenerative agriculture), and perhaps more expensive credit to other industries (diary farming). This can be used to create the option for people to use their skill’s for socially and ecologically useful work.

Personally I think credit guidance is a great idea. Though for it to work, every major industry will need to co-operate with the public to some extent in order to figure out what the numbers need to be. This will require some force from the public. Historically, the farming lobby in NZ has not been willing to pay a nickel for their emissions, despite the fact that the 5th Labour government offered to use such nickels for investment in regenerative agriculture research (Knight, 2018).

But credit guidance would also fix many cost’s by addressing them at the root of the system. If people in agriculture are paid so that they can make as much money growing potatoes as they would with diary farming, then the cost is addressed in the development bank, rather than cleaning up rivers, prosecuting polluters, and so on.

Summarizing, credit guidance offers the following:

Full employment with skill matching. People in destructive industries are given a way to use their skills for socially and ecologically useful work.

Fixing the issues at the root of industrial failure (finance), rather than putting plaster’s over the problem way down the line.

An example of (2) could can be seen in Stiglitz and Stern’s idea that greenwashing should be combatted by independent scrutiny:

Good information on products and companies will be an important part of this process, including independent scrutiny to expose “greenwashing.”( Stiglitz and Stern).

In my view virtually all advertising is greenwashing, because it’s premised on the message that people should consume more, which is bad for the environment. Regardless, Stiglitz and Stern advocate nudging. Is there a way to create socially and useful work for advertisers? Yes, it’s called social marketing. Examples of consumption decreases can be seen in labels and adverts explaining the health effects of tobacco. This and other examples,42 in combination with Hickel’s credit guidance idea, would provide a way to phase out advertising and decrease consumption without disrupting people’s lives.

Overall, degrowth offers the path towards a good, and healthy life, with less resource use. Most or many of the cuts in consumption and production should not be seen as making people “poorer”, but in actually will provide opportunities for more rewarding lives. The other thing that degrowth has going for it is the moral argument.

Strategic Response for Achieving the Common Good.

That said, green growth pathways as described would in my view be a significant improvement over the current system. Before any green growth or degrowth implementation actually happens, there has to be mobilization of society around the common good (and not idiosyncratic interests that few care about), in order to use the state for public spending. This is a numbers problem.

The discussion on common ground between green growth and degrowth is an argument for high tolerance for each other’s position. I’m not saying that you should give up truth or criticism. But just to try and be as cooperative as humanly possible with people that have difficult points of view. I am definitely not saying I am good at doing this, but it has to be done.

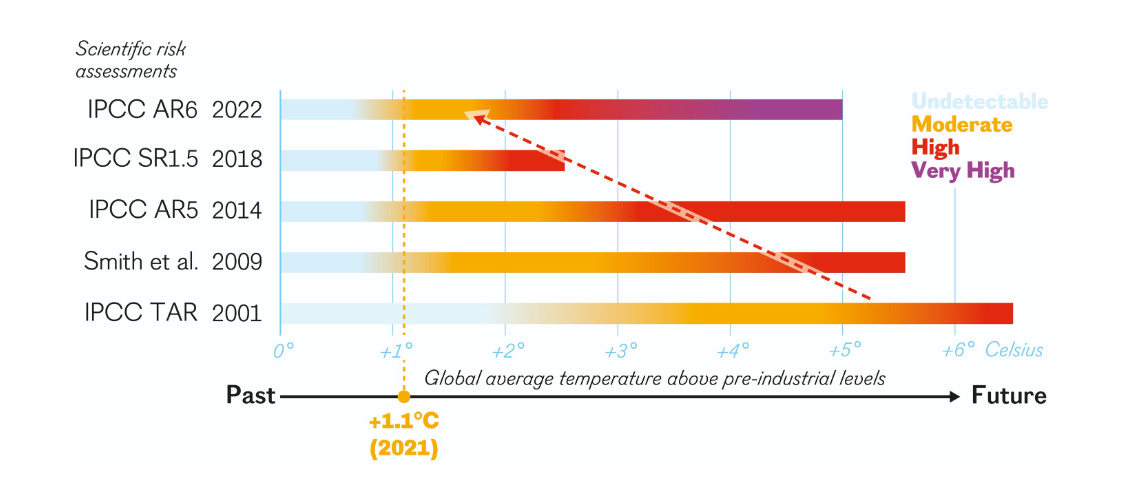

The current range of debate in climate science is as follows:

Each consecutive IPCC report has lowered the risk threshold for a cascade of tipping points, now considered to be high risk at 2 degrees. We are currently heading towards 2.7 degrees by 2100 under the climate action trackers projections. The most pessimistic scenario is that a cascade of tipping points would unleash rapid warming, up to 4-5 degrees Celsius. Scientists call this the “hothouse earth” scenario.

The sharper the decline in consumption and production, the more we minimize the risk of this horrifying scenario. We also sharply mitigate the damages from the optimistic scenario.

Since this is the case, one might argue that the morally right thing to do may be to go beyond what degrowther’s have typically argued for, which includes ending all waste, but also rationing and downsizing to the point of very low levels of subsistence for everyone on earth.

High levels of rationing were politically acceptable during World War Two, at least according to polling (Cox, 2020). This is a data point for arguing that it’s at least possible, under certain conditions, to convince society of extreme degrowth. However, it would be deluded to think the world in its current state is close to those conditions.

So now we are forced to consider the strategic point of view. The opinions on tactics for political activism are something to be very open minded about. I base a lot of my views from people more experienced and knowledgeable than me, but also from studying power.

Consider ExxonMobil. Their tactics for preventing action on climate change may be useful for understanding how to mobilize it. After all, it’s reasonable to think that political domination may have an equal and opposite reaction that can reverse it. When you look at it from ExxonMobil’s point of view, their strategy of domination is to do anything that prevents political action on climate change. This gives rise to a wide range of tactics.

Essentially, Exxon’s strategy has been to tailor many different denial narratives to the culture’s that they work best on. They ranged from deflection, to pseudoscience, to pretending that it would harm the economy, that “natural gas” is an intermediate step. Or that carbon capture storage is somehow a reliable assumption for the future.

The lesson to be learnt here might be that green growth, and degrowth stories will work on some cultures better than others. Pushing both narratives simultaneously could be beneficial because it has a larger aggregate effect, maximizing exposure and political interest. Personally, I think that pushing green growth can help degrowth. If it gets someone interested in the ecological crisis and politics, then it’s more likely to expose them to degrowth ideas. That is, in fact, how I came across degrowth.

The Tactic of Voting:

The other tactic from Cambridge Analytica was to manipulate non-voters, de-politicized people into voting Trump. The left should then try to get young and poor people interested enough to vote. To do that, you will have to get them interested in politics first.

Some hypotheticals to consider:

If the Greens get 20% of the vote, then we get a left-wing government. If they get 35% of the vote, then they dominate labour. If they get 50% of the vote, then national and act parties probably will either disband or be forced shift far enough to the left that they adopt the Green parties current policies.

The green party advocates both a Universal Basic Income and Job Guarantee. For 20 minutes of effort, these policies alone would provide substantial life improvements for most of society, but especially the poorest quintile.

Once response to all this is to say that I don’t want to vote because elections are a sham. They are rigged with public relations. This is all true, and I wish more people said it. But it does not in any way imply that you shouldn’t vote. The act of voting still has a consequence.

Societal Tipping Points

Degrowther’s should (and mostly do) recognize that getting the public to rally around the common good and use the state for their interests is their best shot at getting the public to hear them. Both camps advocate restoration of cultural institutions, such as expanding research and development, education, and reducing wealth inequality. All of these factors are good for protecting unorthodox opinion, and the public’s ability to defend themselves from propaganda and deflection.

For example, reducing wealth inequality diminishes the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the media. It would also increase social cohesion, and narrow the cultural divide between rich and poor. This in turn could be compounded by funding more into sustainable urban designers, who have been figuring out how to increase interpersonal interactions through building design and increased common spaces. See how the societal tipping point could work now?

Under the green growth pathway described by Nicholas Stern, we would spend around 2-3% of GDP per nation on public investment into research, development, public transport, renewables, and whatever else is good for the planet. To get to this point, society has to overcome the ideological barriers such as “fiscal responsibility”, and other deceitful arguments being used to say we cannot use the state for the public interest.

This propaganda campaign to prevent people from using the state for the public interest is the biggest propaganda campaign in human history. It’s been sustained, basically non-stop, for the last 100 years. The Atlas Network that the left has focused on is really just a fraction of it. Once you go through it, you can see that each consecutive generation has inherited an increasing accumulation of ideology seeks to convince them that it’s impossible to have nice things.

What this means is that myself and younger people inherit generations upon generations of lies, and cannot possibly work through all of them. The strategy then, should be to focus on the important ones, and ignore the rest, and ignore the deflections.

What are the deflections? They are culture war narratives. Like demonizing rich individuals and their extravagant consumption habits. Taylor Swift’s plane use was a target of this for example. Focus on institutions, not individuals. The example of “independent scrutiny of greenwashing” given above is another deflection. There’s no such thing as independent scrutiny, and the average person gets exposed to thousands of adverts a day. It’s wasted time.

What are the important lies? I just mentioned one. It is not hard to see that “fiscal responsibility”, deficit hysteria, and arbitrary limits on public debt are probably the most important lie’s to expose. That is because the majority of the solutions to societies problems require turning on the government faucet. The problems that are alleviated with public money include climate, ecological, health, and inequality, social atomization, and democracy. All of these problems have economic solutions.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has been a useful economic theory that exposes basically all of these lies. One goal of the left, then, should be to try and educate themselves and others about this. Even a basic, superficial understanding of MMT has a lot of value.

The other problem that has to be overcome is social atomization and paralysis that is preventing a revival of a large climate and labour movement, which is needed to pressure the government into adopting this pathway.

Under such a scenario, if we really got to the point where the government was able to spend this much on public infrastructure, it would likely create a societal tipping point that would spread consciousness towards the fact that the more that is spend, the more people will realize that there’s little or no truth behind the deceptions that are holding people back. One comparison we can make here is total war. Clara Mattei sums this up in the post world war one period:

The war had revealed to all—workers and bureaucrats alike—that economic priorities were actually political priorities, and thanks to unorthodox finance, the state could meet political objectives at any financial cost. Indeed, once the gold standard constraint was removed, the possibilities that emerged opened new horizons for social expenditure. Suddenly no expenditure—toward social measures that were within the society’s resource capabilities—seemed beyond financial possibility (Mattei, 2022).

So, in summary, actually getting people interested in politics to the point where they can use the state for the public interest, is what wins the debate here. Put another way, the debate is resolved by creating the economic conditions under which the public is well educated, more trusting, and has more exposure to political commentary. Anything that mobilizes the public towards this end, even if it’s done by people who have never heard of degrowth, should be considered as helping degrowther’s.

Misrepresentations from Green Growth

The tactics from green growther’s have often been to misrepresent what degrowther’s say. This is obviously terrible for achieving political will and their own goals. The general argument’s from green growth scholars are to either (A) say that degrowth would cause political backlash, have an austerity like effect, and (B) say that degrowth should not discussed because it will be associated with austerity.

Green growther’s at least recognize that the need for public support and mobilization:

However, rapid and comprehensive decarbonisation will not happen autonomously. It has to be driven by leadership and public support. Leadership and public support, in turn, require a compelling narrative that can generate momentum (2024, Fankhauser).

I will now start providing examples for the reptilian brained thinking coming from green growth. The criticism essentially boil down to two types:

Green growth scholars misrepresent degrowth, likely because they didn’t even bother to read a single article on degrowth.

Green growth scholars read about degrowth, but will now use mental gymnastics to say it’s bad.

In the case of (1), I include Joseph Stiglitz, Nicholas Stern, Paul Krugman, and Branko Milanovic. Actually I have not seen that Milanovic is a self described green growther, but will include their response here because he’s seen as influential. We can see from reading their criticisms that there are no citations, and have not bothered to even read an 8 page explanation of what degrowth even is, despite having years of free time to carry out this 10 minute task.

Krugman and Milanovic base their understanding of degrowth from reading emails and debating people on social media, apparently. I will just leave examples here, with hyperlinks for people to check if I’ve taken anything out of context:

Misrepresentation One: At the other extreme to those arguing to do next to nothing are those saying that growth should stop immediately… To put the issue in stark form, we surely do not want to get to net-zero emissions by having zero consumption (Stiglitz & Stern, 2023).

What Degrowthers say: Degrowth has a discriminating approach to reducing economic activity. It seeks to scale down ecologically destructive and socially less necessary production ( Hickel, 2021)….